News Feature

The Northern Uganda Dilemma: Government whipped as the ICC gets overwhelmed with people's expectations in the Dominic Ongwen case

A panel of experts,moderated by Daniel Komakech a senior Lecturer at Gulu university. (L-R) apolot (State Attorney), Isaac Okwi, (Justice and Reconcilliation Project), Jimmy Otim (International Criminal Court),Henry Kilama Komakech (International Crimes Division, Sarah Kasande (International Center for Transitional Justice) and Peter Pacuto (High Court Arua). Joyce (State Atorney

State Attorney Joy Apolot was one time handling a case of defilement when the victim questioned why she was prosecuting her husband. As the law would require, court went ahead and remanded the suspect. The girl returned to court bearing her baby in the arms and told Apolot to provide for the baby since she was responsible for sending her ‘husband’ to custody. The judge and the prosecutor were puzzled.

Apolot’s testimony recently before a gathering at Gulu University is a typical representation of the dilemma northern Uganda has found herself in since 2006 when the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) conflict was declared over by government.

The conflict, which lasted two decades and affected mostly the Acholi sub region, was started by the Acholi themselves and most of the victims were their own. Children were abducted and recruited into the rebel ranks. Victims, therefore, became perpetrators. They meted out terror on their own people. Government forces too did their damage as for 20 years they fought a resilient LRA led by Joseph Kony.

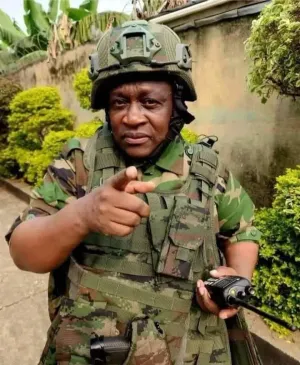

Dominique Ongwen

During that chaotic period crime and general abuse of people’s rights were gross. By the time the war ended, the Acholi were a society torn by forces beyond its own control. Prosecutors have found themselves in a conundrum, having to prosecute people who were also victims of the circumstances.

“There are incidences when the victim becomes dependent on the offender. When you are prosecuting the offender you are prosecuting the victim. There are cases when the offender, on completion of their sentence – apart from those who die in custody – they go back to the community and find the victim. You find the victim crying ‘he is back. What should I do?’” Apolot told the gathering.

The above background lends credence to a process known as Transitional Justice (TJ). This, according to the International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), “refers to the ways countries emerging from periods of conflict and repression address large-scale or systematic human rights violations so numerous and so serious that the normal justice system will not be able to provide an adequate response.” Such ways include criminal prosecutions, truth and reconciliation commissions, compensation measures for victims and other ways that bring about accountability.

The Gulu gathering, convened by the DANIDA funded Building Stronger Universities (BSU) project, brought together lecturers, maters students, and practitioner in the field of transitional justice to primarily share experiences, generate new knowledge, as well as find new areas for research. Some experts were critical about the way the Ugandan government was responding to the northern Uganda crisis, accusing it of lacking the political will to implement transitional justice.

Sarah Kasande, ICTJ Head of Office for Uganda, said that the deficiency stems from the government operating in an “authoritarian context.”

“What is the political incentive for this government which by all intents and purposes benefits from the declining rule of law and a shrinking civic space? How does it pursue transitional justice?” She asked. “There is no genuine interest to address what happened in the past; the aspect of pervasive impunity, the continuing human rights violations accompanied by failure to carryout effective investigations,” she said.

Kasande, in addition, claimed that the “elite” had hijacked Uganda’s transitional justice process and were dragging their feet while the victims continued to suffer.

“The elite driven technocratic process gives them an opportunity to drag on. You can’t talk about transitional justice outside the National Transitional Justice Policy [2019], which is a fallacy. It takes four years to pass the policy, it will take another five years to pass the legislation,” she said.

She said the policy lacked an effective framework to handle transitional justice issues and stressed the importance for the transitional justice process to be “citizen driven”

“One of the glaring absences in the policy is the aspect of institutional reform. What happens where you have a structure where there is no accountability whatsoever?” She questioned.

The International Criminal Court (ICC)’s trial of Dominic Ongwen, an ex-commander of one of the LRA brigades, who has been on trial in The Hague since the end of 2016, represents some hope for reparation for the people in northern Uganda. The closure of the case is expected before the end of 2020. The challenge, however, is that the court is overwhelmed with people’s expectations.

“If found guilty the victims are expected to get reparation. As of now the total number of victims (those who participated) in this case is 4,107. When you look at the context in northern Uganda that is another area of conflict,” the ICC’s Jimmy Otim said.

Otim added that there is a lot of bitterness in the community. “When you talk about Dominic Ongwen they say ‘that one is in a five star hotel let him come here and suffer with us. They are not saying imprison him. The other question is why only the LRA [is being tried] and not the Uganda Peoples Defence Forces (UPDF),” Otim

William Balikuddembe

William Odinga Balikuddembe, a Science journalist/Head of Research at the National Unity Platform (NUP)

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published.