News Feature

Rediscovering the benefits of crop diversity in the face of growing food insecurity and malnutrition

How a community is addressing food and nutrition insecurity by reviving cultivation of indigenous crops

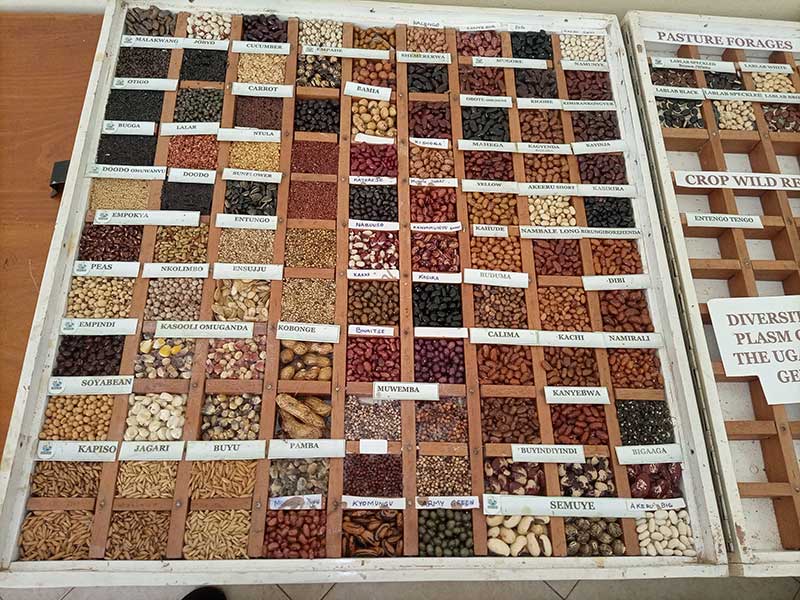

A display of some of the unique seeds that are being stored at the National Plant Gene Bank in Entebbe

My late grandmother Yayeri Nakiganda used to keep different varieties of beans around her courtyard. The varieties came in different colours and of different size and appearance. Some were shrubs like Nkolimbo, (pigeon pea) others were climbing like Bigaaga. Some were black and people referred to them cheekily as Obote, but majority were multi-coloured and we loved the resultant rainbow beauty of the regular harvest season.

Because many of the varieties matured at different times, and had a marked tolerance to drought and heavy rains, Jajja Nakiganda, as we fondly referred to her, hardly ran out of sauce due to prolonged bad weather conditions.

Before cooking, Jajja would harvest different fresh beans and vegetables like Doodo (Amaranth) or young pumpkins. She would wrap the beans and the fresh vegetables separately in a banana leaf, but steam them together with the food. When the food was ready, she would gently smash the freshly cooked beans and then the greens, separately before she would mix them, add some ingredients like onions, salt, spices and ghee and a bit of water to make mouth-watering sauce. This not only ensured she saved energy by cooking the food and the source together, but it also provided us with an assured source of nutritious food.

On hind sight, this golden generation of diversity, has, inevitably perhaps, all but disappeared across most villages in Uganda, due to rapid urbanization and commercialization of agriculture. Markets with fewer varieties have replaced the backyard garden that many of us grew up sourcing our food from.

Although advancements in science have led to the discovery of newer and more nutritious varieties with vital trace elements such as zinc and iron, commercialization of agriculture, coupled with climate change, have exposed millions of people to the vagaries of uncertainty that come with changing prices.

The current food crisis in the country and other parts of the world, have forced policy makers and other players in the development arena to rethink approaches to address the growing food insecurity and malnutrition by specifically focusing on access.

As the international community commemorates World Food Day on October 16 under the theme; Leave NO ONE behind, we’re reminded of the benefits of the benefits that are associated with food diversity and initiatives that have been taken to mitigate the effects of agricultural commercialization and climate change, by ensuring a healthy balance between the new and the old ‘indigenous’ varieties in an effort to achieve food and nutrition security.

Lack of access to seed is one of the critical obstacles to food security in Uganda and globally, especially for majority of Ugandan farmers who have land to grow food.

While most of the crops that our parents and grandparents raised us with have since disappeared, it is worth noting however that all is not lost. In fact, deliberate efforts have been taken at International, National and increasingly at regional or even village level, to conserve indigenous varieties through promotion of seed banks.

In Uganda, the vital process is championed by the Plant Genetic Resources Centre (PGRC), a part of the National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO) based at Entebbe Botanical gardens.

The centre boasts a huge stock of diverse crop varieties numbering over 7600. Some of them are stored in deep freezers to ensure long-term integrity of the seed, while others that cannot be kept in freezers, are kept in the field such as those at the various NARO research institutes.

More gratifying perhaps is the fact that the national gene bank offers free access to some of its genetic resources to members of the public for planting, upon request. This helps to expand access to the diverse food resources which boosts food and nutrition security.

On my part, I was pleasantly surprised that I was successfully reunited with some of the rare beans like Bigaaga that I ate while growing up.

In collaboration with the International conservation agency Bioversity International, PGRC has helped to expand its mandate and popularize the work of conservation by setting up community seed banks that play vital roles including conservation of a wide range of crops. Such platforms offer farmers an opportunity to share ideas on diverse crops they grow as well as provide farmers an opportunity to access seed on credit while also acting as a dissemination point where new varieties from government research institutions are released and tested for taste and other attributes.

Members of Nakaseke Community Seed Bank are trained on how to raise seed to maintain their seed bank

Nakaseke Community Seed Bank in Nakaseke town council, Nakaseke district of central Uganda is one of those seed banks that were established with the help of Bioversity and NARO, to help the community members to preserve their seed.

Opio Aisteen, the Coordinator of Nakaseke Community Seed Bank, says the facility has provided members and the wider community with varieties that have unique attributes such as greater tolerance to extreme weather conditions such as drought and heavy rains.

“It was discovered that some farmers in Nakaseke had tried to preserve some of the rare varieties of beans like Nakyewogola, Obote. With land donation from Buganda kingdom, Bioversity and NARO, Nakaseke Community Seed Bank was established in 2014 to help the farmers store their seed,” recalls Opio.

The seed bank has proved even more critical in cushioning farmers against the double effects of drought and rising prices.

“There are varieties that have greater tolerance to drought than the common beans grown these days. For example, varieties such as Kaasiriira and Kayinja, will yield something even in very dry weather conditions. Secondly, some of these indigenous varieties can still give you something, even when you don’t use fertilizer,” says Opio, before adding that for many of the indigenous varieties, their authentic taste is something to behold.

Credit seed

Access to quality seed is often a major obstacle for many farmers in Uganda, more so in tough economic situations as the one that has obtained in the country since the COVID-19 outbreak more than two years ago.

For members of Nakaseke Community Seed Bank, who number about 120, they’ve found a way around this challenge.

According to Opio, they have a system of credit seed, where a member borrows seed from the group, and returns twice the volume of what he/she took after harvest.

Seed handling skills

Distinguishing between grain and seed in many parts of Uganda’s farming community remains something of challenge among farmers.

Thankfully for residents of Nakaseke Community Seed Bank, and nearby areas, experts from NARO regularly meet farmers to educate them on how to handle seed, including checking basic aspects of seed quality, how to raise good quality tree seedlings through grafting to take into consideration the region’s strong tradition on mango fruit production.

If history is a guide on the benefits of training farmers about seed production and handling, the current success of NASECO, formerly a community-owned initiative that was transformed into arguably Ugandan’s biggest seed company, suggests that the sense of awareness could translate into more entrepreneurship in this area.

Indeed, as Opio observes, the skills gained have inspired some of their members to start individual seed banks in their homes.

It’s not only the indigenous varieties that are kept and promoted. As Opio notes, the community often receives new seed varieties that are released by NARO, which helps members to share and adopt the new at a much lower cost compared to the market rates.

“The store is managed by PGRC through a committee that includes people who are charged with different tasks, such as seed distribution, maintaining standards and quality. For example, if someone is lent seed, they will have someone supervise the exercise until it is harvested to ensure high quality,” Opio explains.

While adoption of improved seed is generally encouraged as a way to boost output and incomes of farmers, experiments such as the one in Nakaseke has shown that maintaining diversity that includes the old and the new varieties has numerous benefits especially in helping farmers face more uncertain price shocks and adverse weather conditions that are likely to increase with climate change.

Besides, the indigenous varieties often play a critical role in the development of new varieties as researchers resort to the indigenous varieties to obtain unique traits that they include in new varieties.

Comments