Columnists

2016 Poll Petition test for democracy vis-a-vis elections

One of the tenets of Western democracy is the holding of regular elections. It is presumed that the validity of politicians assuming leadership in their countries, is to address the franchised citizens, on how they will solve the pertinent problems affecting that citizenry.

It is further presumed that the citizens will have a choice by the use of ballot papers where they will indicate their choices and put that paper in a box – uninfluenced and undeterred.

Through imperialist and colonial attachments, this democracy has percolated to African countries that were largely chieftainships. And because of further attachments through financial institutions, that the Western countries control, they urge the practice of elections as both a carrot and stick, if the African countries want to access that finance.

Therein lies the paradox of the ideal and the practice. It is also in this that differences emerge on how the West and Africa implement the ideology.

African politicians-cum-leaders, with a historical hangover of chieftaincy, which influences their unfettered desire for the trapping of chieftaincy, and the modern craving to be seen to be democratic, in order to grab the finances to bolster their power, has led to the bending the democracy rules in such a way as to attempt to fool all the people all the time.

That is why the Western countries introduced the practice of “election observers”: they do not trust Africans holding a democratic (transparent) elections.

Again, in order to circumvent transparency in the whole exercise, Africans very conveniently refer any dispute over the polls, to another aspect of the tenets of Western democracy – the courts.

And again, the African has very cleverly anticipated the Western insistence, that they respect the decisions arrived in the-otherwise vaunted institution. But the election observers have not anticipated that some African leadres can adroitly evade the ideal – especially, through bribery influence-peddling and force .

In both the 2006 and 2011 general elections, Kizza Besigye, the runner-up to the winner, President Yoweri Museveni, went to court and challenged the validity of the declared results.

In the first instance, the ruling was that, despite the skewed elections, the result still stood. In the second case, the judgment was that; skewed, but any difference in the declaration would bring destabilization.

Both observations failed to pointedly and single-mindedly address the factor of the genuiness of polling – that is why the elections are there, after all – not subsequent and assumed aberrations.

This time round, Besigye has refused that route, leaving Amama Mbabazi, who was declared a very distant third, to contest the outcome of the elections. Going by the former rulings, what chance does Mbabazi have, given that he garnered only 1.3% (or is it 3.4%, depending on who has tallied), of the popular vote?

Unless of course, this time round the court considers the actual exercise of polling – or the lack thereof – of the actual observable results as “declared” and “received” (if they were) at the Electoral Commission.

Still, this gives an idea of the deviation from the validity of the actual polling. But another problem is cropping up here. There is a claim by the Mbabazi lawyers that their expected witnesses are being arrested (exercise of power), thus denying them their day in court.

Debunking the 2011 ruling in reference to destabilization, what are we observing in the streets of Kampala?

Where are the “crime preventers” who were trained in the run-up to the elections? Presumably these would be the fellows who would be patrolling the streets to assure the citizens of tranquility. But in a show of force, it is the military that is visible. Is this a sign of stability?

The main problem of elections in Uganda is the factor of incumbency. Unless Parliament addresses the issue and amends the constitution on that score, the country in simply wasting its time and the borrowed resources on holding general elections.

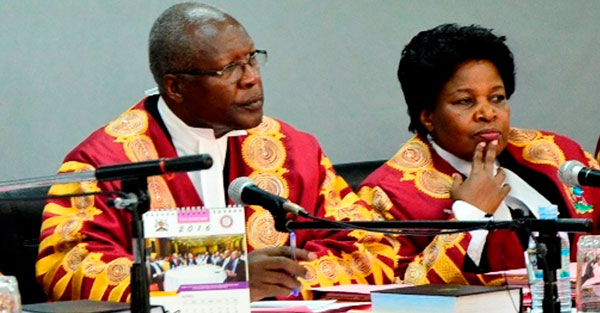

Ideally, it should be the Chief Justice who should assume the reigns of power just before, during and immediately after elections. She/he would be the one to transfer power to the in-coming president.

That assumes that the three arms of government would have been involved in the selection of the Chief Justice. Also, that the predominant parties, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and the prelates would be included in the exercise, to assure impartiality in that office.

The Court would then constitute the Electoral Commission and the exercise of elections – after the sitting president has stepped aside – to allow the exercise a smooth run.

That would go a long way for the incumbent not to exercise influence and control over public resources, other institutions and media in her/his favour. This is what the Tenth Parliament should do.

However, given the gerrymandering prevalent in Uganda’s politics, this is too much to hope for. szumuz@yahoo.com

Comments