Columnists

The Economy in 2016

We started the year with unanswered questions; we are ending it with unconvincing answers!

Many Ugandans cannot wait for 2016 to end. We started the year on tenterhooks, and by extension the country, remain intact with Amama Mbabazi, the immediate former NRM Secretary General and Prime Minister, appearing on the same ballot paper with his long-time boss and friend? We wondered.

Will Kizza Besigye allow Mbabazi to run as a single candidate or the vice versa? Suppose either of them won the election, will President Museveni stand at Kololo and hand over power that he obtained after putting his life on line? Suppose Museveni won again, will things just pass the way they have been turning out since 1996? All these very difficult questions rang in the heads of every serious Ugandan.

I often tell my friends, I hate politics! Imagine the time we spent, the calories burnt, the cognitive resources we squandered, and the anxiety we endured running around thinking about these and other related questions.

Imagine the young men and women who lost their lives in the streets battling with very uncompromising police! Imagine the amount of GDP we lost carrying out experiments whose results we already knew!

Yet I am also not so naïve to think that had we not carried out these experiments, things would have been better. Whenever I read reports from North Korea, Burundi, South Sudan and other countries where politics is a no-go-area, I settle for what I have to endure every five years.

Self-inflicted economic distress

But when shall we say bye-bye to these uncertainties that every five years bring our economy to its knees? Last week I wrote about the state of our ‘sick’ economy. I used simple real life indicators to show that Uganda’s economy was not working well — the light traffic on roads, Ugandans turning down wedding invites, bars closing early, empty shelves at big supermarkets, and so on.

Undoubtedly, the questions I mentioned above that Ugandans were asking themselves at the beginning of this year, must have contributed significantly to the prevailing economic situation. Therefore, I think I am right to say that our economic distress this year was mainly self-inflicted, especially if you factor in other national weaknesses – failure to implement what we set ourselves to do, the rampant theft of public money; we know the usual list.

Admittedly, however, a number of the economic woes were beyond our control. Think about the difficult regional environment (South Sudan, Burundi). Think about the uncertain global economy (the stunting China, lower commodity prices, the BREXIT, and other geo-political events). Don’t forget the internal calamities (the unusually long dry spells across the country, a chaotic election and its aftermath, and the two Kasese uprisings).

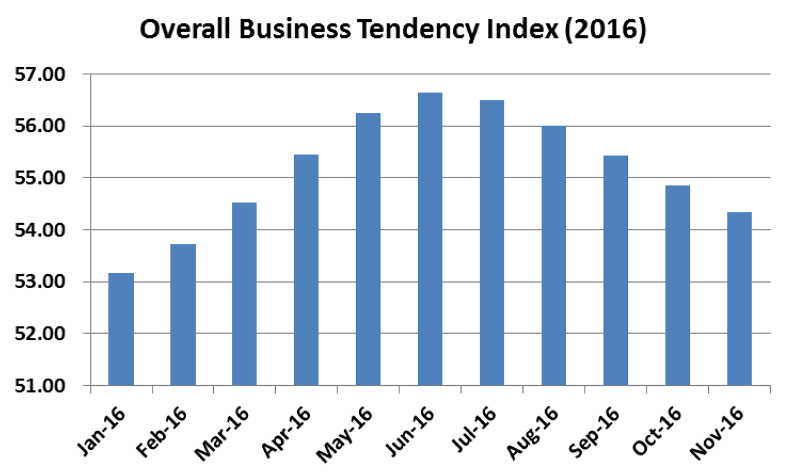

Therefore, it is not surprising that we are ending the year with waning optimism. Bank of Uganda (BOU) compiles what they call the “Business Tendency Index” (BTI). It measures the level of optimism that business owners and executives have about current and expected outlook for production, order levels, employment, prices and access to credit.

The index ranges from 0 to 100, where figures less than 50 imply negative expectations or pessimistic view about the prevailing and ensuing business situation, while scores greater than 50 imply positive expectations or optimism among the business practitioners.

Bad economic prospects

Using the latest figures from the BOU, I plotted a graph of the overall BTI for 2016. The graph resembles the side-view of a roof of a house. Although, overall, business owners and managers have kept an optimistic view of the business situation throughout the year, the level of optimism that was rising between January and June, has since waned.

Mr. President, Ugandans are getting more worried about the state of the economy as we approach the festive season. Now, this is uncharacteristic of Ugandans. Normally people are cheerful towards Christmas. Before we explore this is the case, let us look at other parameters used to measure economic and business situation.

Another important indicator used to forecast future economic activity is the “Leading Economic Index” (LEI). It ranges between 0 (worst prospects) and 1 (best prospects). Currently, Uganda’s LEI is estimated at 0.47 which implies bad prospects going forward. Actually experts project that our LEI will stagnate at 0.48 between 2017 and 2020.

The third indicator commonly used is the “Changes in Inventories” (CII), used to determine the stocks of goods held by firms. These stocks have been rising over the years, an indication that the economy has not just weakened but has been flagging since 5 or 6 years ago.

For example, last year the CII increased by UGX 197 billion, compared to the average of UGX 156 billion held between 2008 and 2015. However, the average for 2016 is estimated at UGX 171 billion, which is lower than last year’s although significantly higher than the previous inventories.

Why is business doing badly?

The fading optimism has mainly been caused by the poor financial situation, particularly the difficulties in accessing credit, faced by businesses throughout the year. Actually business people are pessimistic that this particular aspect (credit access) is not likely to improve in the near future.

Looking at the performance of credit that went to private sector in 2016, I understand why businesses are worried about the future of our economy. First of all, the average rate that banks have charged businesses that borrowed their money in 2016 is 24%. This interest rate is obscene! I don’t know which type of business these banks expect one to invest in and raise all that money.

In a piece I penned recently about the Crisis facing commercial banks, I pointed out that as long Ugandan banks continue charging these obscene interest rates they should expect to lend only to people with higher risk of defaulting, either through outright ‘adverse selection’ or through forcing ‘good’ borrowers to invest in riskier projects (moral hazard).

What’s the solution?

The only solution to the prevailing situations is banks (and their regulator and government) realising this plain commonsense and work towards reducing the lending rates. What needs to be done does not reside in NASA archives; it is within the banks, the BOU, and the government.

The banks, beginning in 2017, should learn to reward their ‘good’ borrowers by lending them at lower interest rates. The BOU, on the other hand, should relax its obsession with ‘inflation targeting’ and reduce the Central Bank Rate (CBR) to levels that are not prohibitive for banks’ desire to reduce the lending rates.

I know inflation is a terrible thing – actually a cancer if it gallops – but the prevalence of cancer has not stopped us from building factories, driving cars, eating fried foods or even drinking alcohol.

By the way, although the BOU has, somewhat, responded by reducing the CBR from 17% in January to 13% last month, it is not a guarantee that banks will also respond and reduce their interest rates significantly. It hasn’t worked before; it doesn’t require a genius to know that it will not work even next year. We need a serious study and action on the effectiveness of the CBR. Well, it may be an effective medicine in fighting inflation, but we need to look at its ‘side-effects’.

Government; stop borrowing

For government, kindly make one resolution for 2017: no more borrowing from banks. Mr. President, the average rate at which your government has issued its paper (the three tenors of treasury bills) this year was 15%. In behavioural economics we call this methodical madness. There is no way you can expect banks to lend money to business people when government (whose risk profile is zero) is willing to take the same money at such high rewards to the banks.

No wonder, commercial Banks’ lending to private sector has stagnated this year. Actually, the credit to manufacturing sub-sector has reduced from 15% in January to 13.7% in October. Yet it is this sector we need to develop to expand our export base to support the value of the shilling.

This year, export earnings have reduced both in value and monthly receipts. In the past ten months we have earned only $2.4 billion from our exports (led by coffee, $270m; Oil re-export, $98m; fish, $96m etc.). The monthly coffee exports have reduced from $32 million in January 2016 to $24 million in October.

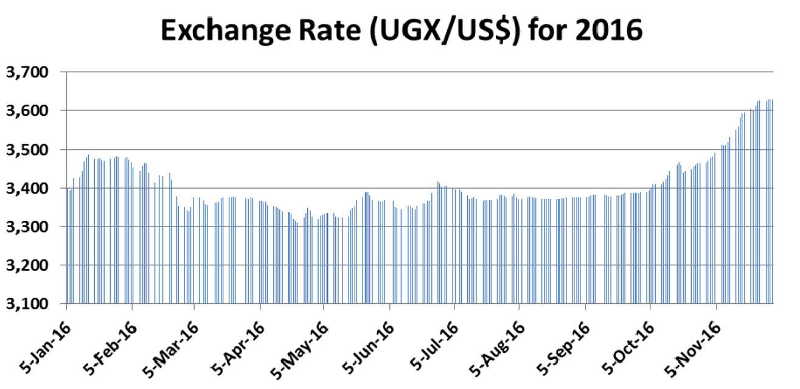

Yet the import bill keeps on growing. In the period under review, total merchandise imports cost us $4.2 billion, implying a balance of trade deficit of nearly $2 billion. This is the reason the shilling has lost a lot of value. Future trends indicate the exchange rate will uncharacteristically keep rising into the New Year (see the graph below).

Normally, the shilling around this time has historically tended to appreciate, thanks to our brothers and sisters ‘sweeping’ abroad, who bring in a few dollars when they come back for the festive season. This year, as the graph shows, the exchange rate has been depreciating since October and it is showing no signs of any significant appreciation in the coming few weeks.

I know the authorities at the BOU and at Ministry of Finance are trying hard to craft solutions. We need to rebuild people’s confidence by finding ways of boosting consumer spending, raising take-home pay for workers, and reducing inventories. Mr. President, all these point at one remedy: put money back in people’s wallets. How? I will attempt a few ideas next week.

Comments