Columnists

Uganda’s economy; 31 years of moving in circles

President Museveni and his bush war comrades including Kizza Besigye (circled) in Kampala in 1986

There are two conflicting things lawyers often say. The first is, agreement or memoranda] in writing.” The second is, “If only my enemy had sent me a letter.”

We have all heard about the beauty of not putting it in writing. Why? Because your past often comes back to haunt you. This wisdom is as old as civilization, yet it appears secluded for the brave men and women who liberated our Pearl from the bad regimes of 1970s and early ‘80s.

Mr. President, while in the bush (1981 – ‘86), you and other colleagues of yours in the National Resistance Army (NRA)/National Resistance Movement (NRM) wrote what you called “The NRM Ten-Point Programme”.

You stated Point No.5 thus, “Building an independent, integrated and self-sustaining national economy.”

Under this point, the NRA/NRM decried the economic structure of the country you had inherited, which was dependent on the export of a few unprocessed crops – coffee, cotton, tea, and tobacco (also known as the CCTTs).

Ten-point programme

You also criticised the past governments, and the rest of Africa, of the failure to build manufacturing industries that use locally produced inputs.

You identified four steps your government was going to take to change the situation. These were: (1) Diversification in agriculture away from the CCTTs; (2) An extensive import substitution in order to reduce the import bill, especially of basic consumer goods.

Others were, (3) Processing of export raw materials to add value: and (4) Building of basic industries like iron, steel, and chemicals.

Mr. President, reading the ten-point programme (TPP) and other policy documents, as well as the various speeches you gave in the early days of your presidency (compiled in your 1992 book “What is Africa’s Problem”), one can easily see why the NRM was a very popular party.

You and your liberation war comrades had set out to do all the right things. The abovementioned four ‘steps’ you identified were well sequenced and pragmatically structured. They were not only desirable goals; were also easily attainable.

80% of exports still agricultural

The question, therefore, should be: why has the NRM failed to achieve this beautiful point in their programme?

I know you and some of your supporters would want to disagree with the verdict that the NRM has failed to “build an independent, integrated and self-sustaining national economy.”

Let us get some of the facts right: currently, Uganda’s total gross domestic product (GDP) stands at UGX 93 trillion (about $26 billion), having risen from about UGX 14 trillion ($4 billion) in 1986. This is a sixfold increase in Uganda’s GDP in the past 31 years. Kudos to NRM.

However, although the GDP has expanded quite impressively, the structure of the economy has not changed much.

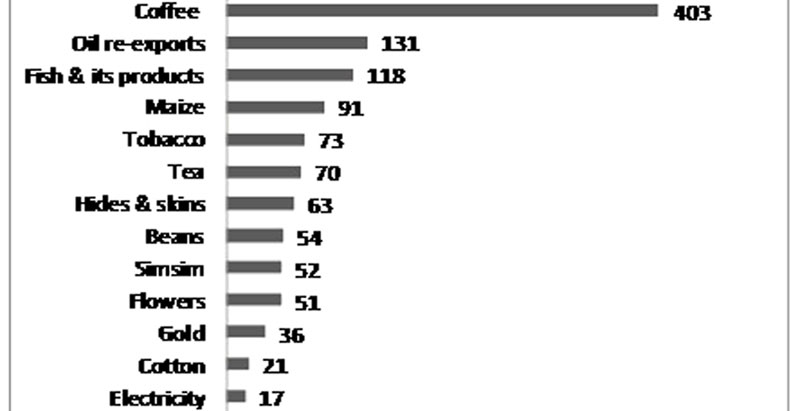

Like it was the case in 1986, nearly 80% of Uganda’s exports today are still agricultural commodities, with coffee alone contributing nearly 20% and over a third of foreign exchange earnings.

Moving in circles?

Other key foreign exchange earners for Uganda include maize, tobacco, tea, beans, simsim, cotton, and others (see Figure 1).

This clearly shows that we have not succeeded in “processing of export raw materials to add value” (the third step to achieve Point No.5 of the TPP).

Figure 1: Uganda’s top merchandise exports in 2015 (in million US dollars)

Although, over the past three decades the NRM government has tried to diversify the agricultural exports away from the CCTTs – by introducing non-traditional exports such as flowers, fish, hides and skins, maize, as well as improving tourism – little has been achieved worth celebrating after 30 years.

If I were to award marks for structural transformation of the economy, I would give the NRM 30% which is 20% below the pass mark.

Actually, if one considered the recent change in policy, one may be right to say that we are moving in circles. Mr. President, under the Operation Wealth Creation (OWC), you directed government and the hardworking men and women in military uniform to refocus on the production of coffee and tea.

Where’s import substitution?

This is a contradiction of the first step (diversification away from the CCTTs) under point No.5 of the TPP, and in also disagreement with economic theory that posits that the CCTTs may not be as lucrative as commonsense suggests since they have a low income elasticity of demand.

The CCTTs do not take advantage of rising incomes of people. When people’s income rise, they do not substantially increase consumption of coffee or tea or tobacco, the way they would buy say manufactured items. A billionaire drops one teabag or spoon of coffee in his cup, as does the low income earner seated on the next table.

Nevertheless, for low technology and subsistence producing countries such as Uganda, it was imprudent to abandon the CCTTs and encourage people to produce annual crops (maize, beans, simsim etc.) and ‘experimental’ crops (vanilla, pepper, cocoa etc.). Therefore, it is a wise move to correct this mistake.

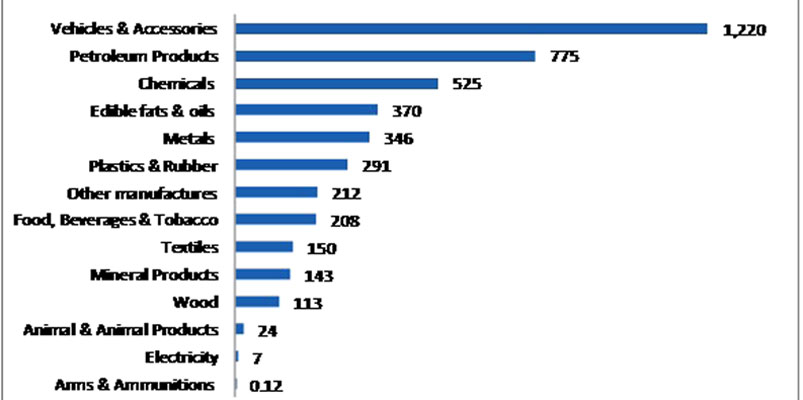

On import substitution (in order to reduce the import bill) the NRM has failed flatly. You found Uganda a net-importer. In past 30 years, Uganda has not only remained a net importer (of very low-skill manufactures such as toothpicks, candle wax, fruit juices, bathing sponges and all the sorts of things we import), our trade balance (BOT) deficit has grown from UGX 298 billion ($83m) in 1986 to UGX 8,280 billion ($2.3 billion) in 2015.

Figure 2: Uganda’s top merchandise imports in 2015 (in million US dollars)

What needs to be done?

As a result of this huge BOT deficit, the value of the shilling has greatly been eroded. In 1986, it required a Ugandan to pay only Shs.44 to buy one US dollar; in 1990 (when the first Forex Bureau was opened up in Kampala, starting the liberalisation process) the same Ugandan paid Shs.436 for a dollar. Today, we are required to pay Shs.3,600 to purchase the same dollar! This is obscenely ridiculous.

The NRM’s failure to change the structure of the economy towards self-sustaining, is on account of a number of reasons. I will attempt to delineate them by citing what needs to be done to attain Point No.5.

First, the NRM needs to stop writing policies, and start implementing what is already on the shelves. When I was invited to Kyankwanzi (at the National Leadership Institute) in mid last year to speak to the cabinet, the NRM top leadership, and the Permanent Secretaries, I told them that the only policy that they needed to write was the policy on policy implementation.

Secondly, the NRM needs to carry out an urgent reform in the civil service and politics of this country. Currently, there is a chaotic political-administrative interface. The political leaders and technocrats can no longer work together. We have conducted research for an international organisation (thus reserving its copyright) that clearly shows little will be achieved if the status-quo is maintained.

The NRM needs to wake up to this reality. Restructure government by closing some ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs). There is a lot of duplication of roles and budgets, which has led public servants to pursue ‘mandates’ instead of the national interest.

Private sector-led strategy?

Thirdly, in order to develop the agricultural sector (which will be a prerequisite for industrial and economic transformation), the government needs move away from the current supply-side focus to a demand-driven strategy to elicit farmers’ interest and responsibility.

Government is wasting a lot of money on planting materials going to people who either don’t need them or lack the incentive to use them productively. In addition, people will not commercialise agriculture on land whose rights are not protected. You must title people’s land to strengthen their rights such that they spend less time protecting land instead of producing.

Fourthly, the NRM needs to invest in industry. Let us forget about the so-called private sector-led strategy. No country has ever been industrialised by private sector-led growth strategy. I know someone will quickly think about the industrial parks and other things government is currently doing. These are scattered efforts which won’t achieve much.

Contrary to the dogmas of neo-liberalism (worshipped by the economists at Finance and Bank of Uganda) where private investment is supposed to be “good” while state investment is supposed to be “bad”, state investment has played a significant role in almost all the world’s fastest economically transforming countries.

Although everywhere is different, East Asian economies have shown the world that economic success requires both the ‘invisible hand’ and the ‘visible hand’.

Finally, to build an independent, integrated and self-sustaining national economy, the NRM will need a lot of Andrew Carnegie’s wisdom. He said, “As I grow older I pay less attention to what men say. I just watch what they do.”

As leaders of the NRM celebrate the 31st anniversary of their stay in power, they need to do one thing: stop talking and get down to work. Stop reminding us how this is a kisanja hakuna muchezo; let actions send the message. May I say, happy anniversary to Mr. President and the entire NRM fraternity.

Comments