Business

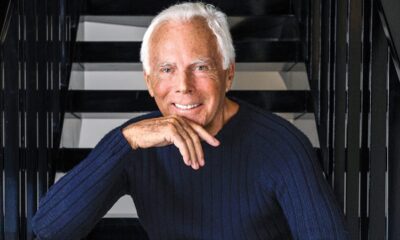

Giorgio Armani’s Will Opens Path to Partial Sale of Fashion Empire

Giorgio Armani, long known for his refusal to cede control of his iconic fashion empire, had consistently pledged not to hand it over to a French conglomerate. In 2016, he even created a foundation to prevent any future break up or takeover.

However, prior to his passing at age 91 earlier this month, his stance had shifted.

In a will drafted in March and released on Friday (Sep 12), Armani instructed the Giorgio Armani Foundation to sell a portion of the company he established in Milan five decades ago.

The revelation surprised many in the Italian fashion scene especially because two of his three preferred buyers are French: LVMH, L’Oréal, and EssilorLuxottica. This gives Bernard Arnault, who leads LVMH, a potential opening to acquire a highly sought after Italian brand.

The disclosure has effectively launched what could become a high-stakes competition to invest in one of the most prestigious fashion houses in the world, a business analyst’s estimate to be worth at least €7 billion (US$8.3 billion; S$10.6 billion).

Owning a share of Armani, one of the largest privately held luxury companies globally, has long been considered a rare and valuable opportunity in an industry with limited targets of its caliber.

The announcement drew swift and enthusiastic reactions from the named suitors.

L’Oréal, which has collaborated with Armani on its beauty line for nearly four decades, expressed it was “touched and honoured” by the mention. EssilorLuxottica, headquartered in Milan but planning a move to Paris, said it was “proud” to be considered and would “carefully consider the opportunity”.

Nevertheless, insiders from both firms noted that, despite the flattering acknowledgment, an outright acquisition was unlikely.

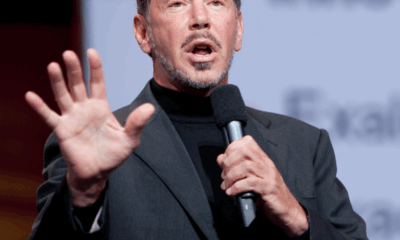

For LVMH, the landscape is different. Executives in both Milan and Paris told the Financial Times that Armani would be a strong fit for Arnault’s portfolio of brands. Sources close to LVMH confirmed that Arnault has been interested in Armani for some time.

Arnault himself said he was “honoured” to be named and compared Armani’s creative legacy to that of Christian Dior.

“If we were to work together in the future, LVMH would be committed to further strengthening [Armani’s] presence and leadership around the world,” he added.

Three Milan-based luxury insiders admitted they were taken aback by the inclusion of LVMH in the will. One cited the 2023 documentary Milano. The Inside Story of Italian Fashion, in which Armani firmly ruled out selling to a French entity. “It’s just unthinkable that only a few years later, out of all people he mentioned Arnault as his preferred buyer,” the individual remarked.

The will also instructs Armani’s successors including trusted lieutenant Leo Dell’Orco and family members, to consider other companies “of the same standing” and to prioritize those that already “entertain partnerships” with Armani’s business.

The initial plan is to sell a 15% stake within 18 months, followed by a second sale of 30% to 54.9% to the same buyer within three to five years, according to documents seen by the FT.

Under the terms of the will, the Giorgio Armani Foundation whose stakeholders include Dell’Orco, nieces Roberta and Silvana, nephew Andrea Camerana, and sister Rosanna must retain a minimum 30% ownership in the company.

For potential investors, Armani’s licensing deals especially its long-standing beauty partnership with L’Oréal are highly attractive.

The Armani Privé fragrance collection, launched in 2004, sells at around €300 per bottle, while Acqua di Giò, a staple since 1996, remains among the top selling men’s fragrances worldwide.

Still, the existing licensing agreement with L’Oréal, which extends until 2050, means buyers won’t be able to fully monetize that segment of the business in the near term.

The diverse nature of Armani’s offerings ranging from EA7 sportswear and Armani Exchange casualwear to high-end Armani Privé could also present a challenge for buyers.

Some industry insiders argue that the wide product mix under the Armani name has weakened the brand’s identity. In addition to fashion and beauty, Armani also operates luxury hotels, restaurants, and a high-end home furnishings line.

Pierre Mallevays, co-head of merchant banking at Stanhope Capital, noted that while Armani performs well as an independent brand, “it’s hard to see a big strategic buyer being genuinely interested in all of its operations”.

Although LVMH is widely seen as the frontrunner, its premium market focus suggests limited interest in Armani’s lower-cost product lines, which generate a substantial portion of the company’s €2.4 billion annual revenue.

Moreover, LVMH prefers to control product distribution directly, a sharp contrast to Armani, whose goods are often sold through third-party retailers and sometimes at discounted prices.

A leading executive in the Italian fashion world said any strategic buyer would likely need to wait before making decisions about how to handle Armani’s various divisions. “That’s what the prospect of buying Armani would look like,” the executive said, a holding pattern before acting.

If the sale strategy does not materialize, Armani’s will also leaves room for a potential IPO. This would place the company alongside other listed Italian luxury brands like Prada, Brunello Cucinelli, and Moncler, where founding families have typically retained controlling interests.

In interviews with the FT before his death, Armani made it clear that preserving his legacy was his top priority.

Following the will’s publication, the executive committee at Armani issued a statement saying the foundation would serve “as a permanent guarantor of compliance with the founding principles”.

Two fashion industry executives suggested that Armani’s choice of LVMH, L’Oréal, and EssilorLuxottica may have stemmed from their size and financial strength, key to ensuring the brand’s stability and future.

Luca Solca, an analyst at Bernstein, said that Armani’s decision to pursue a partial sale made sense, given the brand’s long-term needs: “There is a lot of work to be done to ensure the continuation of the Armani brand legacy.”

“Armani liked to run his own business and there is an element of vanity when you are a very, very important designer, you don’t want to be part of a much bigger group. But today we are seeing a more rational side,” Solca added.

Comments