human traffickingFeatures

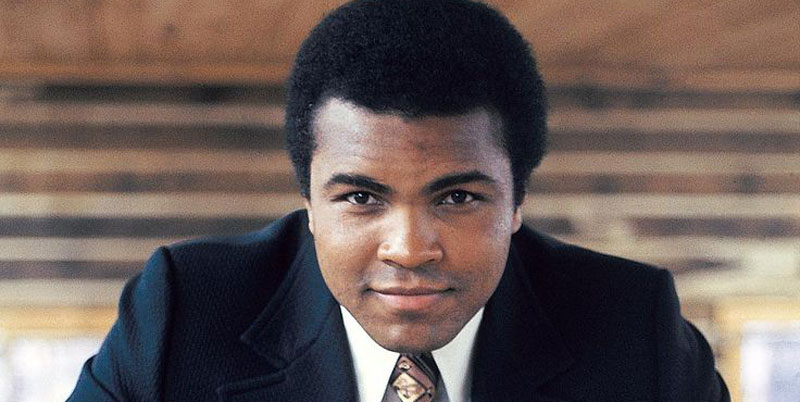

The Greatness of Muhammad Ali – the Legend

Budini (Drew) Brown was always present at Muhammad Ali’s ringside. He was Ali’s corner man, shadow and stuntman. He strutted at Ali’s side of the ring during the bouts, shouting encouragement to his heavyweight boxer boss and goading Ali’s opponents.

“Dance, Ali, dance,” he would egg on, if he perceived that Ali was slackening in his rhythmic footwork shuffling and body gyrations to the creation of Ali’s own poetic insight: “Float like a butterfly; sting like a bee.”

This, Ali’s observation of nature and translating it to a prize fight mantra, was a phenomenal show of intellect that captured Ali’s early realization in the 1960s, that he might have to do something unusual to rise above the race limitations in his 3302 Grand Avenue home of Louisville, Kentucky in the American mid-west.

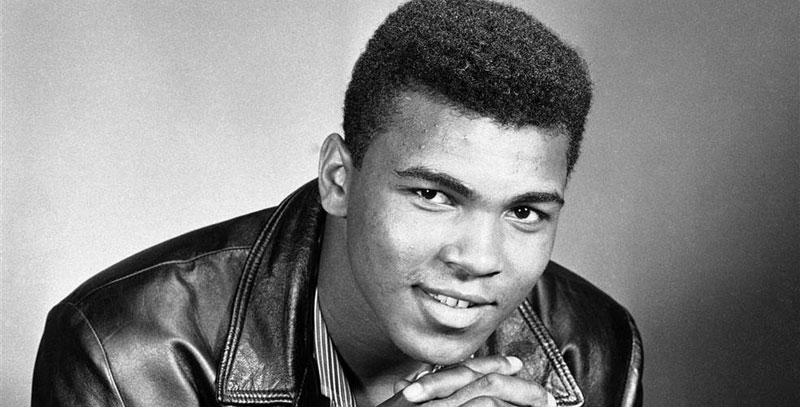

The son of a painter, Cassius Clay and Odessa Grady Clay, Ali was born Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr. in 1942. At only 12, he was introduced to boxing when he reported the theft of his bicycle to a passing Policeman whom he told that he would “whup” the thief if he got him. The Policeman took Clay to the local boxing gym to sharpen his fighting skills if he had to beat thieves.

The rest was then there for all to see and witness; which for Ali, ended at a Scottsdale clinic, Phoenix in Arizona, last week when he died at 74.

Instead of beating thieves, that gym training took Clay Jr. to the Rome Olympics in 1960 where he won the gold medal in the amateur light-heavyweight division. From then on it was meteoric but brief rise in his early fighting career. After Rome he immediately turned professional and beefed-up the-then rather slender frame of 6’ 3” to over eleven stone.

Clay immediately won reknown and recognition far beyond his nascent years by utterances and behavior. By his own admission he was studious and inquisitive and kept asking, especially his mother, why they (the Blacks) were regarded and treated as second-class citizens. His academic pursuit ended only at the Louisville High School.

These were the heady days of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Elijah Muhammad, Ralph Abernathy, Louis Farakhan, Al Sharpton and the Civil Rights Movement. Into this mix Clay Jr. was to make his mark, probably far beyond these other people and in dramatic fashion.

The first things he did to draw attention to himself was to buy a Flamingo pink-coloured Cadillac Convertible and to throw his Olympic gold medal into the local river.

At 18, this was sensational. Of course, this was done in the full view of the media, especially TV. The adroit exploitation of the media was to become Ali’s hallmark. As novelist, Stanley Crouch put it: “Everything Ali did was big… when he was right… or wrong… when he embarrassed… or, when he inspired us. That is why he remains the king of the world.”

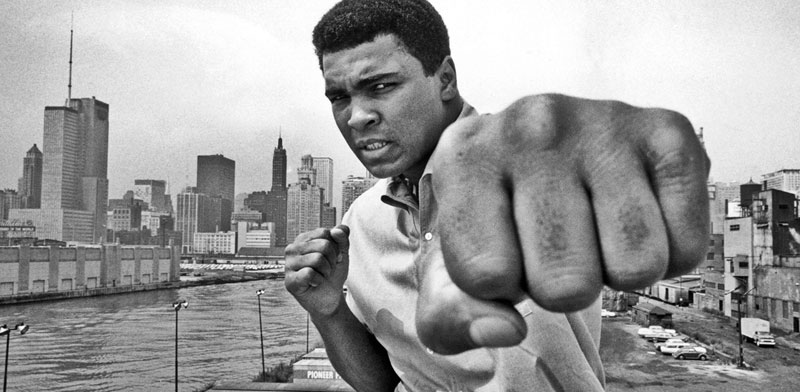

The next thing was to capture the heavyweight championship of the world. He was young, brash and strutting and many regarded him merely as the “Louisville Lip”, a talkative self-promoter who called himself beautiful.

And he was going to come against among others, “the big ugly bear”, fearsome, Sonny Liston, then heavyweight champion of the world, who had a ferocious knockout punch. Many, who did not like Clay’s attitude, were happy that finally this boxing upstart was going to meet his nemesis in 1964.

His style of boxing had not been seen before in the ring. Early on when his trainer, Angelo Dundee, witnessed the “dancing”, he tried to dissuade Clay out of it, but he failed and instead Dundee said that he did everything possible to refine the style; dancing, dropping arms, weaving the head out of punches and coming back with lightening punches of his own, thrown from all angles. This was the butterfly and the bee!

At the Miami Beach Convention Hall, in Florida, Liston was pummeled, stung and knocked out in the seventh round. It was almost unbelievable. Cassius Clay Jr. 22, became the youngest heavyweight champion of the world. Before, during and after the fight, Clay taunted Liston.

And the next day, he taunted America. At the headquarters of Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam on Chicago, Clay announced his conversion to Islam from Christianity. He took the name of Muhammad Ali, which he said Elijah gave him. Asked why he dropped his Clay name, he said: “That was a slave name; I am no longer a slave.” He was now priming himself to be the “Greatest”.

That act and talk infuriated White America and its establishment at the time. But Ali remained undaunted. He said he was not a reverse racist; he was “America”. This was Ali’s dramatic entry into the center of the Civil Rights Movement and the campaign for racial equality; but it was not arrogance but humanism. He was cocky, reassured and carried his message with poetic innuendo.

And he had used the medium of heavyweight boxing to get his telling message across to wide American public; and the world began to take note of the brash, young and “beautiful” greatest world heavyweight champion.

He was now getting idolized and reviled in equal measure. His “pattern of beauty, grace and bravado” was both overpowering and engaging. It was only a matter of time before he would clash with the establishment with reference to his sensibilities as to how Black Americans were treated.

That came in the form of the Vietnam War. In 1967 in Houston, Texas, Ali was to be drafted into the US Army to fight in Vietnam. He refused and the consequences were dire for the 25-year-old champion.

The New York Athletic Commission that sanctioned the professional prize fighting stripped him of his title and he was tried and sentences to five years in prison for “dodging” the draft. He never served the sentence as his lawyers fought the conviction on appeal.

Ali did not budge from his position even when he clearly lost all revenue from promotions, endorsements and being the champion. The divergence and disagreement with the White American establishment of the presidencies of Lyndon Johnson s and Gerald Ford was now clear to anyone.

His statement on the Vietnam War and America’s involvement in it was unequivocal. “I ain’t got no quarrel with the Vietcong. No Vietcong ever called me, ‘Nigger’,” he growled. But White America did!

he establishment was incensed; but the Civil Rights Movement had got a champion who could encapsulate the racial differences in vivid and pithy language. Ali almost eclipsed the other campaigners of the Movement and got into the center stage of the campaign for equal civil rights. All along he never claimed Black supremacy over White but of equality; that is what marked Ali as a champion for the humanitarian issues in the racial divide.

For the next three and half years, Ali was on the backburner of boxing, but he continued with his Civil Rights exhortations and appeals against his conviction and unjust treatment in being stripped of his title. Eventually he won his case and was allowed to continue with his boxing career; but by then the title had long gone to someone else – Joe Frazier.

When he returned to the ring in 1970, he was slower and heavier; and initially he was not able to reclaim the heavyweight title. But Drew continued to urge dancing at the ringside corner. Poetically, Ali now added that he “rustled like silk and hit like a stone”. He became more colourful: he added into his fighting attire shoes with tassels which shimmered as he danced. But again the championship moved to someone else – George Foreman.

Ali became more strident, talking himself into a contest with Foreman; that he alone was the greatest, that these fellows were pretenders who had got his belt on a silver platter. He psyched the boxing promoters to schedule the fight in Kinshasha, in the-then Zaire of President Mobutu Ssese Seko Kuku Ngbendu was Zabanga. Ali termed it: The Rumble in the Jungle.

In 1974, Ali got the opportunity; and as he moved into the ring for the fight with Foreman, the crowd sang, “Ali, boma ye” (Ali, kill him). Again, like ten years earlier, nearly everybody believed that Ali would not defeat Foreman. Like Liston of the yore, Foreman, too, had a fearsome knockout punch, he was seven years younger than Ali; and what was more telling was that; no heavyweight boxer before had lost the title and regained it.

The three and half years of internment now clearly showed. Ali had lost some of his fleet-footedness. But he had fashioned a plan and a way to beat Frazier. He called it: “Rope-a-dope.” It involved letting Foreman come at him with the heavy punching while he hung at the ropes most of the time, absorbing most of the blows on the body but covering his face from most of them.

Ali only showed very few flashes of his former dancing and stinging like a bee. But it worked. In the eighth round Ali knocked out the tired Foreman in dramatic fashion.

For the first time in the history of heavyweight boxing, somebody had regained the title: and it was Ali. His claim of being the greatest was no longer hype but reality.

Yet he had failed to beat Frazier in their second fight although Frazier had then lost the title to Foreman. It still rankled that he could not claim the greatness until he had subdued Frazier, among all the other fighters at the time. That prompted the rematch in Manilla, in the Philippines the next year in 1975. Ali termed it: The Thrilla in Manilla.

In all probability, this was Ali’s epic fight; and it was a brutal punch-sapping 14 rounds of the 15 rounds bout. At the end of it both Frazier’s eyes were closed, and he could not see. Besides he was so spent that he could not get up for the last round. For the victor, Ali, he said that this was the fight he rated as coming “close to death”. Both fighters ended in hospital thereafter, Frazier for more than a week. The thrilla cemented Ali’s greatness in the ring.

He fought a few more times to notch up 61 fights, 56 of which he had won, but it was now merely lackluster. His fight career came to an inconclusive end in 1980, as signs of Parkinson disease started to show in his movements and his slurring conversation. Many said, but others dispute that the on-set of the disease was as a result of the many punches he had taken to the head.

But Ali continued his visibility in public appearances and humanitarian work among which he was inducted to the Boxing Hall of Fame. In the 1996 Atlanta Olympics in the USA, he lit the Olympic Torch in a memorable ceremony.

In 2002, famous American actor, Will Smith, portrayed Muhammad Ali in the film of the title, Ali, directed by Michael Mann. According to the Times magazine, “it brings into its hero’s struggle the mastery of himself and his era. That time included his marriages to Sonji, Belinda and Lonnie, who has survived him alongside his nine children.

Smith and former British and world heavyweight champion, Lennox Lewis, will be among the pall bearers at tomorrow’s burial ceremony in Louisville in which former President Bill Clinton will formally eulogize the fallen Champ and Legend. President Barack Obama is among the galaxy of heads of state to have have sent condolences including such far-flung others like British Prime Minister David Cameron, Afghan President Ahmed Kharzai and Turkish President Rejjeb Tayyib Erdogan, among other world figures. Greatness has come home to roost!

Comments