FOCUS ON PARLIAMENT:

Although Uganda was born as a parliamentary democracy on October 9, there were numerous happenings that cast doubt on the continuation of parliamentary freedom that are worth reflecting on as we mark 54 years of independence.

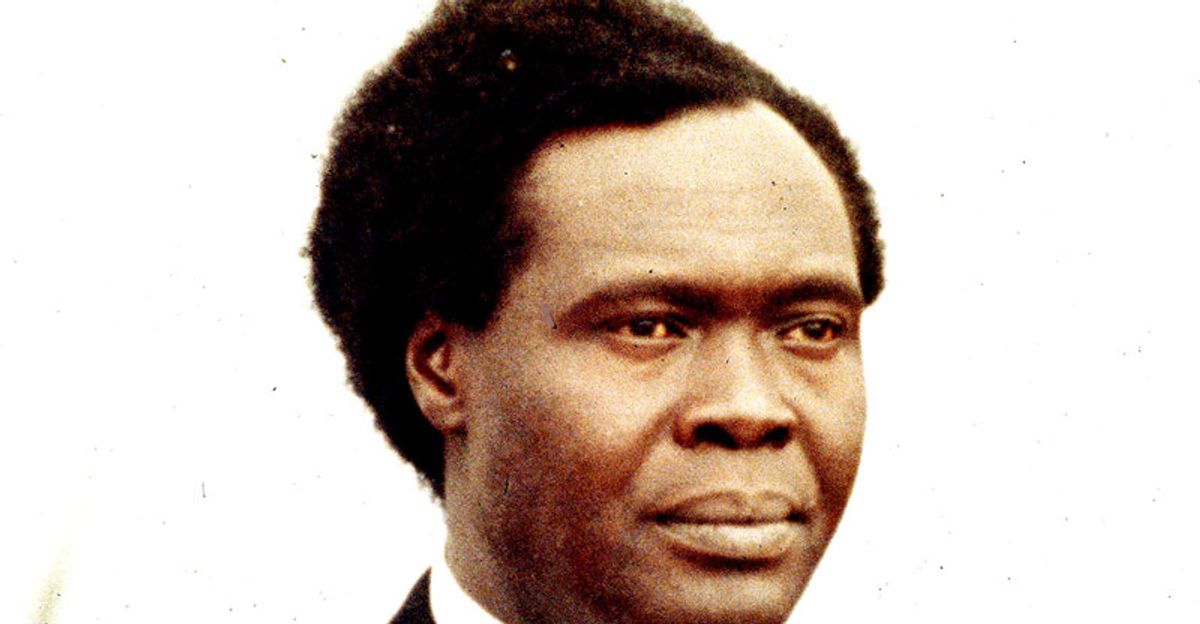

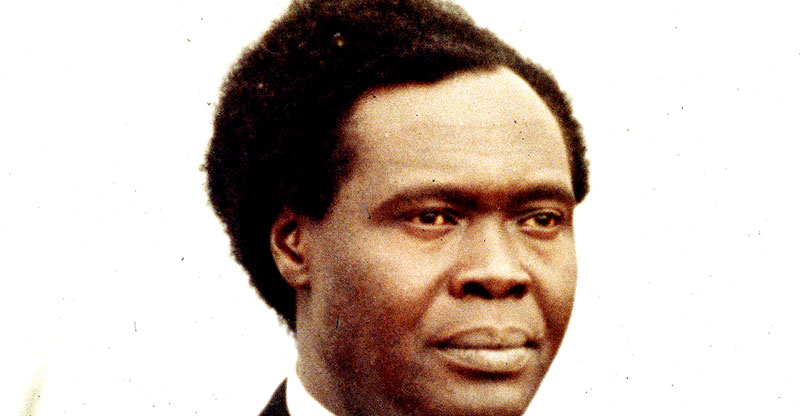

According to the Independence Constitution, the party that won the most seats in Parliament would form government, which is why Milton Obote’s Uganda Peoples Congress, which allied with Sir Edward Mutesa II’s Kabaka Yekka, formed the first government, having edged out Benedicto Kiwanuka’s Democratic Party.

Obote became executive Prime Minister while Mutesa became Head of State. An early complication in our parliamentary democracy then arose because Kiwanuka had not made it to Parliament. Untold acrimony existed between Kiwanuka, a Muganda, and the Buganda Kingdom.

Kingdom loyalists accused Kiwanuka of being insubordinate to the Kabaka and could not envisage a situation where the Kabaka would be lower in hierarchy than a Muganda in case Kiwanuka took over power.

The machinations that ensued before independence therefore meant that there would be no direct parliamentary elections in Buganda, but instead that the members of the national legislature from Buganda would be elected by the Buganda Kingdom Legislature, the Lukiiko.

With Kiwanuka out of Parliament, therefore, and unable to take position as Leader of the Opposition in Parliament (LoP), Grace Ibingira, a DP MP from Ankole, was drafted in as LoP. A jostle for the control of DP would then ensue between Kiwanuka and Ibingira, and when Ibingira lost the fight within DP to Kiwanuka he crossed the floor, along with other DP members, and joined UPC.

That would not be the worst a bit, however. More would come, especially in the events that led to the attack on Mutesa’s Lubiri at Mengo and his flight to exile in London, where he died in 1969. The attack had been ordered by Obote and executed by Idi Amin, his army commander.

The role of Parliament in Uganda’s fledgling democracy was further diminishing by the day as Obote looked to consolidate his hold on power, with the decline reaching climax with the passing of the Republican Constitution of 1967, which came to be regarded as the “Pigeon Hole Constitution”.

MPs got to Parliament to find a draft copy of the Constitution in their pigeon holes, had just hours to debate and pass it. The draft Constitution had been drafted by Godfrey Binaisa, the then Attorney General who would later lead the country for almost 11 months. The MPs, under duress as they faced a real danger of the army moving on them, passed the pigeon hole Constitution.

At that point, it would appear it would never get worse for Parliament. But it did when Amin overthrew Obote in 1971 and decided he needed no Parliament after all. Amin, for eight years until 1979, ruled by decree and Ugandans had no representation at all. The President’s word was law.

Ugandans hated this, and many groups, including Fronasa led by President Yoweri Museveni, tried to fight Idi Amin throughout his rule. There would later be a breakthrough in the fight against Amin when in 1979 he attacked Tanzania, forcing the East African country to invade Uganda and, with the help of Ugandan exiles, eventually throw out Amin.

The attempts to reinstate the country to the democratic path inevitably meant that Parliament would be reinstated, but this could not happen immediately after the war. So the National Consultative Council for a while served as the Parliament until the famous or infamous 1980 elections happened.

In 1980, Obote had returned to Uganda and led his UPC into the elections. Kiwanuka, however, had had been killed in 1972 during Amin’s era and had been replaced by Paul Ssemogrere as DP supremo. The two parties were the major players in the election, although smaller ones like Yoweri Museveni’s Uganda Patriotic Movement also competed.

The election, it has been documented, was riddled with myriad irregularities, including blocking prospective candidates from getting nominated for parliamentary slots to outright swapping of results and everything in-between.

Paulo Muwanga, then the Chairman of the Military Commission who in effect served as the President at the time of the election, finally debarred the Electoral body from announcing results and took it upon himself to release the final results, announcing that UPC had won a majority of seats in Parliament and would therefore form government.

With Obote assuming the presidency courtesy of his party winning a majority, Ssemogerere took up his seat as LoP while Museveni led a group of largely Southern Uganda youth to the bush ostensibly to fight against vote rigging.

With the government facing war from a number of angles, the Parliament was not that effective between late 1980 and early 1985 when another soldier, Tito Okello, led another coup and established a military junta for about half a year.

Lutwa would eventually be thrown out by President Museveni’s forces in January 1986, and Museveni put together a group of fellow fighters and other national leaders into what came to be known as the National Resistance Council, which worked as Parliament.

Museveni himself, who was president and head of the Armed Forces, was also the Chairman of NRC. The chairing of NRC, however, was largely left to Al Hajj Moses Kigongo, the Vice Chairman of NRM and Vice Chairman of NRC, as Museveni took care of other matters of State.

The NRM would be expanded in 1989 when some more members, who had been elected through an Electoral College system, were drafted in. the NRM continued to serve as Parliament until 1996 when the 1995 had come into force and new MPs had been directly elected.

The Constitution was written by special delegates who were directly elected in 1994 to go to what was called the Constituent Assembly and debated a draft constitution that had been put together by a team led by Benjamin Odoki, who would later become Chief Justice.

In the new Constitution, there was an attempt to build in guarantees to safeguard the independence of Parliament by, for instance, prohibiting MPs from crossing party to party during a term of office.

The different Parliaments, since the promulgation of the 1995 Constitution, have engaged with a lot of issues of national importance and, of course, must have made mistakes along the way. It is only natural. But the argument we want to make is that whatever mistakes the successive Parliaments have made, it is still much better to have a Parliament of whatever nature instead of having no Parliament at all. That is the lesson we have learnt from our history since Independence.

As we embark on the 55th year of our Independence, therefore, we should strive to make our Parliament even better, taking into account our history.

Sunrise reporter

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published.