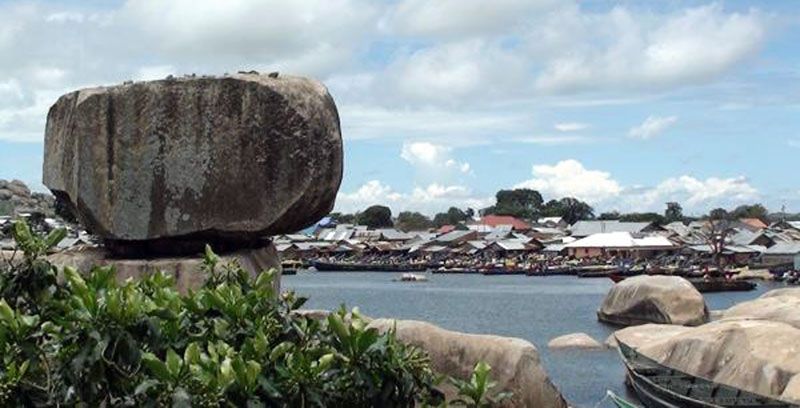

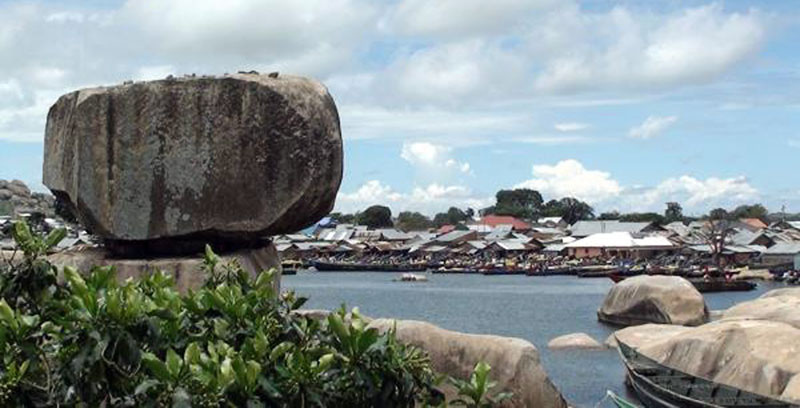

It is a bright morning at Bwondha landing site on the shores of Lake Victoria. I am heading to Dolwe Island, eastwards, on a three to four hour journey by boat to see and touch the rock art and paintings done about 300 to 500 years ago by the early inhabitants of the 4.7 square mile Island famous for the most artistic rock formations.

Golofa, which looks like a storied building; Ndege, in the shape of a plane, Singiro, Bukangawa and Mwango portray the beauty of rock art in pictures. The Island is a place for business.

Professionals such as medics and tycoons in the fishing industry have invested on it. And you find here a mixture of nationalities. An estimated 60% of the population is Luo from Kenya and the rest Ugandans.

Richard Ssebaduka, 51, a fisherman based in Jinja district has lived all his life in these waters. He has seen his business grow from employing one to 200 fishermen. He manages a fleet of 30 motorised boats with about 1,800 fishing nets. His catch averages 100kg per day – he is just one of the many successful people of these waters.

Dolwe is a sub county of about 35,000 people with the most tourist attractions in the Busoga region. To get there you will have to use a boat, unless you have the means to fly.

The buzz at Bwonda this morning indicates that the sailors are running out of time. Time is of the essence else the weather changes and the waves become too big for the sailors to continue the journey.

One could use the faster police marine or light fibre boats but most people are for the wooden boat – it is cheaper. The fare from Bwondha to Dolwe is UGX 10,000. These boats are made in Uganda using imported timber from the Democratic Republic. Neither Uganda nor Kenya has the light wood for the required timber.

“Whoever does not enter will wait for us again tomorrow,” announces the sailor in Lusoga, the predominant language in the region.

As I waited to be carried to the boat, to avoid stepping in water, a woman yelled in Luganda demanding a refund of UGX 500 from the man who had just carried her. “Give me my [UGX] 500. This distance is too short for me to pay 1,000,” she saids

On phone was another woman speaking at the top of her voice in a mixture of Lugbara and Kiswahali. I gathered she was speaking to her business partner in Arua district in West Nile. Language seemed a challenge, hence the mixture.

A boat worker loaded two more 20 -litre cans of fuel on to the blue and white painted boat with dark brown flowery curtains and an iron sheet roof. This was reserve fuel.

The breeze felt cool on my skin. So I wore a jacket. Standing at the shore with my backpack, I watched as countless boys in their youthful days ululated in excitement as they carried more passengers into the 50- seater boat. One of them approached and asked to carry me.

I would have to put one arm by his neck and shoulder. Then he would grab my butt and sweep my feet off the ground. I felt embarrassed. But that was the way to do it. The shore had no gangway to the docked boat. A woman nearly slipped as she was being put in the boat. She was fat. And she was wearing a short green dress. I smiled and the boy carried me.

In the boat were chair and bench seats. I sat at the extreme end to my left. A woman sat behind me with a man who appeared to be her partner. She immediately put her head on his laps fearing to gaze at the water. The woman would vomit all through the journey.

“Can you imagine we trust this piece of wood with our lives on these waves?” A man dressed in neatly pressed blue jean trousers and shirts said in a western Uganda accent as his neighbor turned to look at him with a twisted smile that faded fast from his face.

He signaled for his supplies of assorted drugs packed in a Rwenzori mineral water box to be placed in a safe place – I later established he operated a clinic on the island. More people were added to the boat so that a sit of five people now had seven. Children wailed as their mothers tried to comfort them.

A neonatal mother kangarooed her baby as the boat engine raved, ignited and propelled the pieces of wood forward. The boat went silent, save for the sound of the engine as we headed into the deep blues of the water, into Victoria, the world’s second largest freshwater lake.

The passengers, as though in deep thoughts, kept silent for about 30 minutes as they watched birds freely fly over the waters. Further north, a fisherman cast his net on the lake as a much younger boy rowed the canoe. Fishing is a major economic activity for both Islanders and those on the lake shores at the mainland.

The waves were calm and the coxswain brilliantly beamed, thanking God for the good weather. On a bad day, he would warn the travelers and instruct them to wear the orange lifejackets provided to all passengers accept children whose sizes are not available on the boat.

A mother in front of my seat had a wailing child. To breast feed, she untied her life jacket, positioned the baby and looked into blurred features of Islands formed in the distant. The waters seemed to be touching the clouds as the boat moved further. Conversation returned to the boat. A man, in his 30s, also turned on his hand size radio.

The female presenter, who spoke in Luganda and English, thrilled passengers with her sarcastic prologue of married women who do not care about their hygiene after giving birth. That became topical on the boat.

After about one and a half hours on the water, the boat approached an island. Fishermen were arranging their nets as women washed clothes by the shores. That would be the only stopover, at Masolya Island, the last of the seven islands in Mayuge district.

The boat continued eastwards, at a slower speed because the waves were beginning to swell. The scotching sun poured its fullness on those seated on the left side. I lowered the curtain and took a nap as conversations continued in languages I could not speak – the passengers spoke other languages than English.

The medic had sat next to me on this voyage. He is the one who awoke me to a beautiful rock standing in the middle of the water and further off was a fleet of boats of all colors and fishermen arranging nets. He pointed to another rock on my right, a pile of rocks upon each other in different shapes and sizes.

“That is Golofa. It inhabits most of the gods of this Island,” he said. His name was John Tumusiime. He had lived on the Island for two years providing private health services to the Islanders. “I do not know much about these rocks but all I know is that God created them and many more are that side as you enter the Island,” he added. Tumusiime offered to guide me to the local leaders of the sub county and to the gods of the island who lived in the rocks.

Many locals dispute the Dolwe name, insisting the Island should be called Lolwe, named after apparently its first inhabitant, a Luo, Nyamulolwe, who returned to the Island in the 1970s from Kenya.

The Island fell vacant during President Milton Obote’s regime in the late 1960s and early 1970s due to tse tse fly infestations. Government had planned for aerial spraying of the Island.

The spraying was done during the reign of Idi Amin and two monkeys were later placed on the Island to test whether the area was now safe for human settlement. The monkeys survived and reproduced.

Nyamulolwe then returned and settled with his family in one of the villages, Singiro. He and his wives reproduced more children. Other people joined them. The Island has 14 villages with a sub county local government administrative unit – and the rocks? You will have more of that soon.

Irene Abalo Otto

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published.