Analysis

Crane Bank: What they’re not telling you

Bad habits die hard, and we often regret them on our deathbeds!

A fortnight ago, “Banks risk scoring own goal.” A week later, the first own-goal went in. It was as painful as surprising to the owners of the bank, the owners of the money it was keeping, as well as other well-meaning Ugandans.

Crane Bank has been the fastest growing bank in the country. It has been the “Bank of the Year” for 10 times in its 20 years of existence! It has also been leading the entire pack in return on assets. It made Shs.51 billion in profits in 2014 and a whooping Ushs.80 billion in 2013. At Ushs.1,700 billion, it was the fourth largest bank by asset value.

You may cite so many other nice statistics. It is Ebbe Skovdahl, a former Danish football coach, who once said, “Statistics are just like mini-skirts, they give you good ideas but hide the most important thing.”

It goes without saying that the statistics often cited by the banks and their regulator, the Bank of Uganda — profits and other earnings, number of branches, total deposits, capital assets, liquidity levels etc. — may give us some ideas about the health of the banks but they certainly hide a lot of the important things we need to know.

The fate of Crane Bank provides a perfect laboratory for whoever doubted Skovdahl’s wisdom. Its turning point was last year, when, under the weight of loads of bad loans (popularly known as non-performing loans – NPLs), totaling Shs. 142 billion (over $40 million), the bank descended from its 10 year profitable position into a loss-making bank under bad bankers.

I often tell my students (I specialize mainly in teaching Ugandan Economy) that although Uganda has 25 banks, the problem is that it does not have 25 bankers.

Making bad loans

Few bankers know that the goal of a bank is not only to earn high profits when the economy is booming but also to avoid giving them back when the economy is struggling.

I also teach my future bankers a basic axiom: “When you are in a commodity business, the only way to thrive is to be a low-cost producer. When you are in the business of selling money, you are in a commodity business.”

It is Robert Wilmers, one of most respected bankers, who once wrote, “The only good loan is one that gets paid back.” The world over, banks get in trouble for one reason: making bad loans. It has become a common saying nowadays that no bank fails for lack of capital; bad loans are always the underlying cause.

In my article a fortnight ago, I cited some of the simple-to-understand facts about banking. First, when banks keep interest rates high for a long period they end up lending people with higher risk of defaulting on loans since “safe” borrowers are discouraged from borrowing — the so-called ‘adverse selection’. Second, high interest rates lead ‘good’ borrowers to invest in risker projects, something economists refer to as ‘moral hazard’.

Third, when banks decide to give depositors very low return on their savings, despite the high lending rates they charge borrowers of those savings, they create a ‘principal-agent problem’ that force savers to seek alternative ways of saving other than putting their money in banks.

Fourth, it is well known among bankers that bank confidence is a fragile reed; a bank is damaged by any rumours, true or not.

Predatory lending

These four facts were apparent in Crane Bank’s fate. I will start with the last one. For years, there has been a rumour that Crane Bank engaged in predatory lending – a bad habit among bankers where they structure loans in such a way that borrowers, however much they may want to, fail to pay back such that the bank takes their collateral that is essentially higher in value than the loan.

I have heard so many people whispering how Sudhir, the owner of Crane Bank and the richest man in East Africa, built his empire on seizing other people’s properties using Crane Bank loans as the bait.

I suspect that this rumour, true or not, could have affected the quality of borrowers Crane Bank attracted. It does not require one to be a genius to guess that ‘safe’ borrowers turned their back on Crane Bank and left the risk lovers, who by extension are risky borrowers, to go for Crane Bank loans.

This clearly shows you how the bank ended up being affected by the first and second facts cited above. To be fair to Crane Bank, most banks in Uganda (and in many other countries) are guilty of the same. And like I warned them last week, although bad habits die hard, we often regret them on our deathbeds.

This brings in the role of Bank of Uganda. The BoU behaves like a cigarette company that in pursuit of a fortune lures people to smoke themselves to the grave. And just like the BoU, there is a rich history to the cigarette companies’ behaviour.

Analogy of smoking

In 1949, scientists formally found that cigarette smoking caused lung cancer. As a rule, TV stations broadcasting cigarette ads were required to run anti-smoking awareness announcements.

The idea was that as long as someone is made aware of the dangers of smoking, the consequences would be internalized. Later World Health Organisation (WHO) required tobacco companies to print on the cigarette packets a warning: “Cigarette smoking may be dangerous to your health.”

People continued smoking. Then the WHO thought of another strategy; let each country’s ministry of health become the originator of the warning message, and it should be explicit not the “…may be…” Accordingly, tobacco companies were now required to print the warning: “Ministry of Health warns: Cigarette smoking causes lung cancer, heart diseases and death.”

Did it stop folks from smoking? Never! You find a guy puffing away while holding the packet with his eyes looking at the words, “Cigarette smoking causes lung cancer, heart diseases and death.” Do smokers want to die? Of course not! So why did they continue smoking despite such a scary warning? Because they were addicted. They needed help.

Self-inflicted death

Dear Bank of Uganda, banks are like a smoker. They know that predatory lending, insider lending, bad loans, speculative transactions, reckless lending during election year, and all other sorts of practices could lead to their death. They know all that. Problem is, they are addicted to these vices. They need help.

Charlie Munger, an American businessman, thinks it is worse than I have put it. “I do not think you can trust bankers to control themselves. They are like drug addicts,” he said a couple of years ago.

Research shows that bank failure can be influenced by the regulatory regime. Going back to our analogy of smoking, the most livable countries — where high life expectancy is supplemented by low morbidity rates — have banned smoking or in the process of banning it.

The BoU should emulate this. It enjoys a lot of confidence from the public, and respect from the banks and their equity holders. People have confidence in the BoU because it has been consistent, ethical, and transparent in the way it deals with bank failures, especially since the coming into force of the Financial Institutions

Act (FIA) 2004. No depositor has lost their money as a result of bank failure since 2004. Kudos to the BoU for that!

It has also been somewhat more politically independent. More importantly, the BoU’s prudential regulatory framework is strong. However, to help banks avoid the painful self-inflicted deaths akin to smokers, BoU needs to go beyond prudential regulation — that is, looking into banks’ capital adequacy, asset quality, profitability, liquidity, and market sensitivity).

On top of prudential regulation, banks also need economic regulation. Economic regulation in banking safeguards the social welfare rights of the entire country. The BoU needs to encourage higher competition among the banks, less collusion, and lower industry concentration. If they can’t do this, let them advise government to set up another agency to deal with the economic regulation as they concentrate on the prudential regulation.

Effect on real economy

It is unforgivable that the BoU continued to watch on as Uganda became a country dominated by a few ‘core’ banks. Over the years, the BoU has looked on as small banks (mainly local ones) failed, on the account of bad habits caused by the market structure.

The popular view at the BoU is that the contagion effect of failure of small banks is unlikely to significantly destabilise the financial system since the depositors in the failing small banks will usually run to larger core banks. So they have been closing them with fun.

What the BoU failed to realise was that while allowing small banks to die maintains financial stability, it also makes entry into the core bank category extremely difficult for the small/domestic banks. Accordingly, their policy has created a negative externality of continued high concentration ratios which has made it difficult to raise competition.

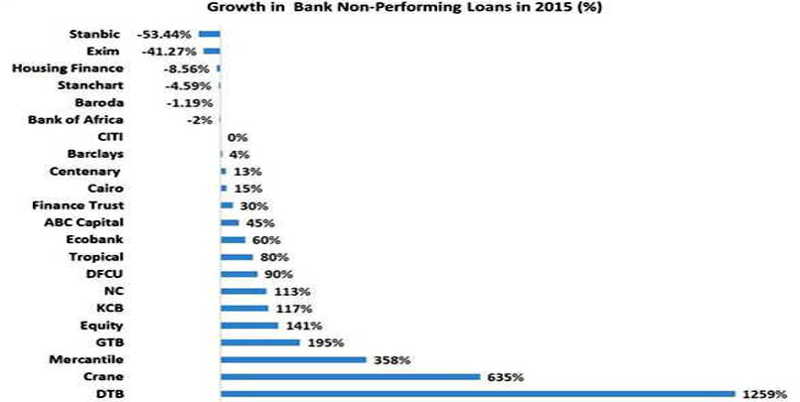

The dominant 5 banks assumed the tripartite doctrines of “too-big-to-fail”, “too-important-to-fail”, and “too-intertwined-to-fail.” Consequently, they became stubborn and ‘reckless’ in their operations. This exactly is the story of Crane Bank. Its ‘exceptional growth’ rate should have raised a red flag. Its loans were expanding too quickly, meaning that the lending officers were probably saying ‘yes’ too frequently. And it was not alone; see the graph (sketched by a friend at EPRC) showing growth in non-performing loans in 2015.

All said, banking is all about confidence in the system. Failure of a core bank such as Crane Bank represents a greater loss for the sector and the economy. It carries wider negative multiplier effects since it indicates regulatory failure and damagingly affects the real economy — loss of jobs, loss of access to capital for SMEs, loss of business for its suppliers, etc.). May I repeat that it’s not rocket science for banks to know how to get themselves out of the Crane Bank mess?

Comments