Can politicians or bureaucrats who own private schools regulate the education sector?

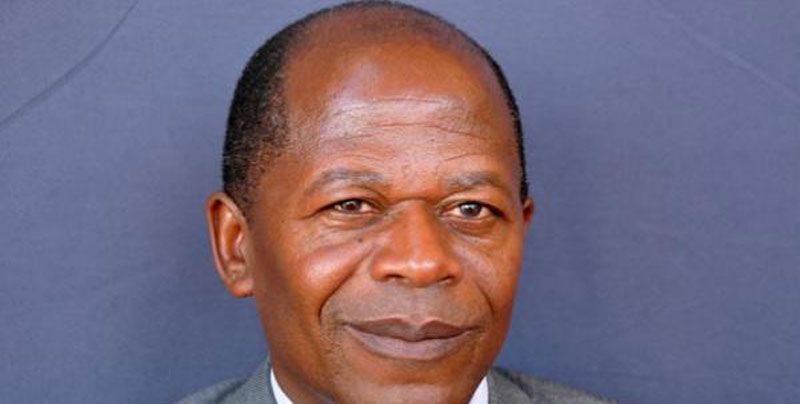

State Minister for Higher Education Dr. J.C. Muyingo. He is the owner of Seeta High Schools. one of the biggest and best performing secondary schools in Uganda that serve mainly the rich upper class of Ugandan society. He faces a serious dilemma of fulfilling his obligations as regulator while also trying to protect personal interests.

This week, social media were awash with outcries over the fees hikes, some of them quite astronomical.

Schools have started charging parents half a million shillings for one pair of uniform and another half a million shillings for ‘development fees’ on top of tuition fees as high as Ushs.2 million.

To explain this, the schools and their regulators cited high cost of production and cost of living as the main reasons. Followers of this column know for how long I have been writing about these issues in these very pages.

Therefore, this week I am not picking my pen to write for the nth time how it is wrong for a school to charge a three year old Ushs.2.5 million to allow them to sketch cartoons or cry around the school compound.

Mr. President, the reason I picked my pen this week was to bring to your attention one fact that could help you understand why you are struggling to achieve most of the national goals. In the end, this piece will attempt a solution making liberalisation policy, particularly in the education sector, work better to maximise welfare of majority Ugandans.

Regulatory capture

As Idi Amin was capturing power in 1971, George Stigler, a Nobel Laureate in economics, was putting his final touches on a paper that nobody could predict would, forty-five years later, starkly define the economic legacy of Amin’s successors.

“The theory of economic regulation” is the paper that Stigler used to introduce a concept ‘regulatory capture’ – a form of government failure that occurs when policymakers or politicians (the regulators) act in ways that benefit the industry they are supposed to be regulating, rather than the public.

A simple example is when a dairy farmer is appointed a Minister of Agriculture and the public expects him/her to regulate the dairy sector, for example, by writing and enforcing a law that would stop dairy farmers from forming a cartel that would make milk unaffordable to many Ugandans.

Similarly, it would surprise few if a bureaucrat at the Ministry of Labour, owning a stake in a manufacturing firm, looked the other way when industry workers complain about low pay and/or poor working conditions.

The general objective of regulatory capture is to redistribute surplus towards the party that is doing the capturing and hence away from some other party.

Price of “Kulembeka”

Uganda today provides a classic example of regulatory capture. Most of the top bureaucrats and politicians in Uganda, who by law and deployment are supposed to enforce rules of the game, are players of the very game.

Not even declaration of conflict of interest would help here. The public and private sectors are virtually intertwined. The ministers of education as well as their bureaucrats own the private schools they are supposed to regulate. Leaders in the health sector own private clinics. The list goes on.

Mr. President, there is something counterproductive that you did for Uganda. When you liberalised the economy, which by the way was a very sensible move, you failed to create institutions to guide the free entrepreneurs as they play their game.

Due to absence of strong institutions to regulate the liberalised and self-serving players, soon you realised that there were serious gaps in the state’s ability to provide services to the people. You resorted to headhunting for key players in the various sectors (education, health, trade, banking) and appointed them as ministers and bureaucrats in the sectors.

Your intention was to leverage their expertise and experience to lead the sectors into service delivery improvement. Little did you know that the very fact that they had invested in the sectors, or were closely associated with investors in those sectors, meant they were already captured.

You even went ahead and persuaded others civil servants who were not active players in the sectors they were regulating to go and do business to supplement their small salaries. Since the 1990s, you have popularised the term “kulembeka” (tapping into resources around you). You called upon your colleagues (the senior politicians) and civil servants to kulembeka. You even started taking them to Rwakitura to learn how to kulembeka.

Leaders serving own interest

In the process, leaders in this country stopped working for the national interest and started serving own interests. This is the main reason economic regulation has virtually failed in this country.

In Uganda, there is misguided obsession with leissez-faire economics. In pursuit of a liberalised economy, the NRM government was advised to leave the private sector alone. The advisers told government that unfettered competition would serve the best interests of society.

As far as education sector is concerned, once private investors were allowed to invest in schools (and health facilities), the government was asked not attempt to regulate or control them. This was a mistake.

Let me tell you Mr. President, there is something dangerous going on in Uganda lately. People have justifiably started to think that liberalisation (the policy of making the economy more market-oriented and expanding the role of private and foreign investment) is bad.

Yet there is nothing wrong with the liberalisation policy. It is the State that has failed to do what it is supposed to do to make the liberalised economy work better and for the benefit of the many, and not the few.

State failure

Today, there is widespread agreement that markets and private enterprises are at the heart of a successful economy, but that government plays an important role as a complement to the market.

Any government that fails to establish and enforce the “rules of the economic game” is not worth governing. What is going on in Uganda today is not liberalisation failure; it is state failure.

Market economics is not about allowing people to make money at whatever cost. Market economics is about allowing people to play a free game of making money without flouting the rules of the game to their own advantage and at the expense of other people’s welfare.

As I have written in these very pages BEFORE, market economics is like football. Football is a free game but it cannot be played without a referee, or when the referee is “captured” by one of the competing sides.

Mr. President, your referees in education, health, trade, banking, agriculture, name it were captured. They run private schools and clinics; while others are close associates of the interest groups in the very sectors they are supposed to regulate.

Chicken and egg case

It is, therefore, understandable that you will rarely hear voices during Cabinet, Parliament, and Ministerial or Departmental meetings suggesting for moderation of the markets. Yet even among the purely capitalist countries of this world – the likes of the U.S. and the U.K – the government regulates in order to make the market economy function well.

In the U.S., fore example, government regulates the prices charged by companies that distribute important utilities and public goods. It also promotes competition. Charging any price that a firm wants for a non-rival good – full of positive externalities – such as education, prevents some people from enjoying the good even though their consumption of the good would have no marginal cost.

Secondly, in well-functioning societies determination of fees takes into account national per capita incomes. It inconceivable to expect parents who earn annual income as low as Shs. 2.4 million ($670 – Uganda’s per capita income) to afford school fees that wipe out their entire income in one term.

Thirdly, it is now common knowledge that any national policy that fails to take account of political economy (ideological, welfare, moral and ethical beliefs of people) is illogical.

It is equally illogical to completely roll back the frontiers of the state in public goods and pseudo-public goods such as education, health, and social security. Public policy actions bear serious political and distributional consequences. We shouldn’t concentrate on efficiency alone.

There are myths that need be interrogated. One of them is that the cost of providing quality education is high and has increased with rising costs of living. This could be a chicken and egg case; what came first?

Economics that works

You could easily find that the very reasons cited by schools to raise fees were caused, in the first place, by the schools themselves arbitrarily increasing fees since no one regulated them. This forced parents to increase prices of whatever they sell to raise the fees, including prices of supplies demanded by the schools. Then the cycle went on unabated since the regulators were in captivity.

Mr. President, to achieve the beautiful goals you and the global society have set, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Equitable Access Policy (providing equitable access to quality and affordable education to all Ugandans), Affirmative Action Policy (supporting more women enrolment, people with disabilities, and students from hardship areas), Education for All Policy, as well as the 1995 Constitution (articles 30 and 34), you need to review your deployment policy.

Stop appointing leaders who own businesses in sectors they are supposed to regulate. The essence of liberalisation is to let private sector channel resources in areas government may not efficiently operate. However, efficiency and equity can only be achieved when the state plays the role of the referee.

While increased choice and competition are good for education, we need to compute the unit cost of providing quality education and compel all providers to charge fees commensurate with the cost plus a reasonable margin them. This is not control. This is not going against the liberalisation policy. This is what is done if private market outcomes are undesirable due to popular concerns of the public. Mr. President, this is the economics that works.

Ramathan Ggoobi

Ramathan Ggoobi is Policy Analyst, and Researcher. He lecturers economics at Makerere University Business School (MUBS) and has co-authored several studies on Uganda's economy. For the past ten years, he has published a weekly column 'Are You Listening Mr. President' in The Sunrise Newspaper, Uganda's Leading Weekly

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published.