Business

Ugandans are more indebted than Uganda

So, why are we more worried about Uganda’s debt yet private debt is rising even faster, and much of it is illegitimate?

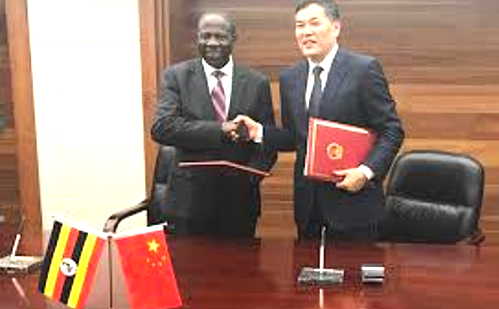

Finance Minister Matia Kasaija (left) has signed several grant and loan agreement with Cinese government officials. This time he signed a grant worth (US$30m) with China’s Vice Minister for Commerce Dr. Qian Keming

Everyone is lately obsessed with talking about the growing public debt in Africa. In June this year, at its 50th Biannual Research Workshop held in Cape Town, South Africa, the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) had a conversation on the “looming debt crisis”.

The conference was told that since 2013, the number of African economies in debt distress has grown from 6 to 15. Data shows 19 African countries have exceeded the 60% debt-to-GDP threshold set by the African Monetary Cooperation Program (AMCP), while 24 countries have surpassed the 55% debt-to-GDP ratio suggested by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as the cut-off point to crisis.

A conversation among economists cannot end without a quick quip, “Africa is heading back to the HIPC era.” HIPC stands for “heavily indebted poor countries,” coined by the World Bank, the IMF and other multilateral, bilateral and commercial creditors in 1996 as an initiative to relieve 36 stinking poor yet heavily indebted countries of the debt they carried.

A similar one called the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) was established in 2005. They literally forgave us the debts we owed them, for we were too poor to pay or to jail. By 2017, they had forgiven the 36 countries debt worth $99 billion, that is, three times Uganda’s GDP today.

Only 6 HIPCs were not African. Uganda was the unofficial chairman of the HIPCs, Tanzania the chief whip for the likes of Rwanda, Burundi, DRC, Ethiopia, Zambia and all the usual suspects.

The fear now among economists and non-economists alike is that we might be heading back to the HIPC days. We have acquired a lot of non-concessional debt with relatively higher interest rates and lower maturities. Africa has also acquired private non-guaranteed debt, now at $110 billion, rising from under $35 billion in 2006.

Highly indebted poor individuals

The real fear is that if African countries fail to pay, this time there might not be forgiveness. That countries might get “jailed” or lose the “collaterals” they deposited.

This is the fuss that keeps economists and media busy. Yet the very folks running around and talking their voices hoarse about national indebtedness – or their acquaintances – are personally indebted to the marrow. They are highly indebted poor individuals (HIPI), and not even eligible for debt relief.

I spent last week in Nairobi with an interesting group of people from all parts Africa (Eastern, Northern, Southern and Western Africa) and beyond. We had a conversation on private debt in Africa that, surprisingly, no one seems interested in.

We were talking about borrowing by individuals and businesses on African continent that has silently gone through the roof, as we obsessed ourselves with national debts. We wanted to know the extent, causes and drivers of private borrowing and lending in Africa.

As we discuss how African countries have borrowed a lot from China, the debt owed by individual Africans and private businesses reached crisis levels. From salary loans to mortgages to school fees loans, crop finance and burial loans, Africans are borrowing their way to bankruptcy. Or is it homeruptcy (since a typical Ugandan keeps his/her money at home in a secret place)?

Getting trapped into debt

We wanted to know, what is the extent of debt among the vulnerable groups such as single mothers and the elderly being targeted by all sorts of financial service providers, formal and informal?

What about debt accumulated by the youth in pursuit of opportunities in the form of SME start-ups and/or sports-betting in the hope that one day they will hit a jackpot and get capital to invest in a more serious business?

What is the extent of debt workers in the informal sector have acquired to expend their businesses operating in the economies of small monies – sharing a few thousands every week? What about the debt smallholder farmers acquiring in an effort to commercialise their rain-fed-pest-infested gardens?

What are the drivers of consumer debt that keeps rising among Africans? A friend working in Nairobi told me she can no longer send her mother money on her cellphone without inquiring first whether her mobile money wallet is “clean”. Her mother is often in debt such that as sooner as the remittance from her daughter lands in her wallet, the telecom company debits the cash.

When I checked with one of my former students working with a telecom company to ascertain the truth, he told me nearly 7 in 10 boda-boda riders have a debt with the company he works for. Those who use boda-boda services as couriers have encountered a moment when you wanted to send the rider mobile money and he stopped you saying, “Don’t send it on my phone; I have a debt.”

Africans (poor and non-poor alike) are increasingly getting trapped in debt, where they seem unable to survive without borrowing. Just look around your small community, starting with your own household; folks cannot survive (or so they think) without getting a small personal, business or corporate loan.

We now have all sorts of loans: quick loan, instant loan, special loan, emergency loan, school fees loan, asset financing loan, business loan, working capital loan, housing loan, makeover loan, agriculture loan, kwanjula (wedding) loan, bridging finance loan (extended to those who want to kick-start a Ponzi scheme), discounting loan, insurance premium finance loan, and so many other forms of loans.

Financial laws protect lenders, not borrowers

There is a systemic pattern where the promoters of financial inclusion perhaps do not want people – they are purportedly “helping” to access credit – to get out of debt. In pursuit of sustained profitability lenders are keeping their borrowers in perpetual debt using subtle and unethical ways.

Although the current highly decentralised credit system hStart slideshowas enabled people – poor and non-poor; men and women; old and youth – to access capital and improve their lives, it lacks ethical and moral dictates of the conventional credit system. In yester years, lenders were concerned with the socio-economic impacts of their loans.

The current system goes to the lowest stratum of society to extract the little that the poor possess, no matter the means – microcredit, mobile lending or any other financial technology (FinTech). As long as there is evidence of some money going to the poor, the lenders will go for it.

If they learn that an elderly woman is receiving some monthly allowance (such as the Social Assistance Grants for Empowerment – SAGE), they start to lure her to borrow. If a young man shows signs of prospering in organic farming, they target him with crop finance he probably doesn’t need. Although the promoters of financial inclusion love to highlight the few success stories of their programs, loads of the poor who attempt to borrow get their fingers burnt.

This is the crisis that we have ignored. The current system has failed to protect the poor, and in a world of do-eat-dog this is not surprising. The financial laws were designed to protect and benefit the lender and not the borrower. Even where a semblance of consumer protection policies and laws have been enacted, their enforcement is absent.

Financial service providers (formal or informal) capitalise on the financial illiteracy and people’s gullibility to fleece them. They hide information or make partial disclosure of information to borrowers to hide unfair contract terms from them.

Borrowing to buy things Gov’t should provide

We are busy celebrating and hyping the increasing availability of credit at household level. Yet it is being fueled by a global phenomenon of financialisation where private capital is seeking to reproduce itself without value creation. In effect this has increased both private and public debts where vulnerable groups face a disproportionate burden of paying back.

These are some of the abusive lending practices in the context of inadequate social protection we were discussing in Nairobi. We were hosted by the Open Society Initiative for Eastern Africa (OSIEA) to have a candid conversation on these issues.

It is abusive lending when people borrow to buy things that government is supposed to provide or ensure that they are provided by the private sector at subsidised/regulated prices. We are talking about public services such as basic healthcare and education, public transport, water and other utilities.

During the FinScope survey last year, Uganda were asked to mention how they finance expenses. The majority (42% or 7.8 million) of them said they borrow to cover the expenses. What are these expenses? Paying school fees for their children and the accompanying opportunity costs, closely followed by medical expenses, rent and utilities (such as electricity, water and energy).

Shoving money down our throats

The neoliberals told governments in Africa that they should leave public and merit goods such as health and education to market forces. People pay millions to deliver babies (by cesarean); pay millions to have the baby, when she turns 4, to attend kindergarten; pay market prices to see a Pediatrician when the baby gets a viral infection; pay millions see them through school; pay millions to rent an apartment to rear the kids; pay full-cost-recovery market prices for electricity, gas and water.

These are the expenses that are forcing people to accumulate private debt at a rate faster than the national debt we love to comment about. Yet the states are expecting the same highly indebted poor individuals to pay for the national debt as well.

There is also a real crisis we must deal with. Financial institutions are setting up people to borrow but make sure they fail to pay back such that they (the lenders) can take the usually more valuable collateral (economists call it predatory lending), or that the borrowers get tied in perpetual debt so they pay the lenders interest forever. All these are happening when the state and its appointed regulators are looking on.

One for the road; who told the world that everyone needs to borrow? Nearly 4 of 5 people from the financial sector that I meet, come to me with one intention: to lure me into borrowing. Why is the neoliberal system so determined to shove money we don’t need down our throats? And it has convinced us to think we need the money! Next week I will tell you what we need to do.

Comments