Climate Change

Karamoja Pastoralists Face Severe Water Crisis as Climate Change Dries Up Dams and Pasture

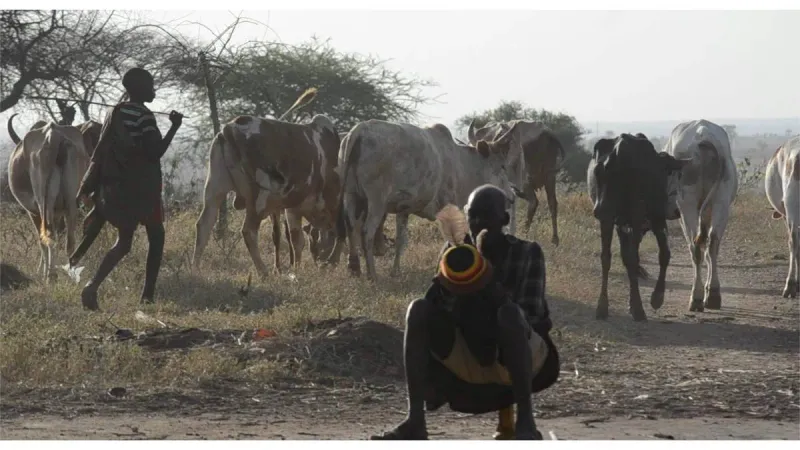

Pastoralists in Uganda’s Karamoja sub-region are facing a deepening humanitarian and environmental crisis as extreme heat and prolonged drought dry up water sources, threatening livestock, food security, and traditional livelihoods. Once sustained by predictable rainfall and abundant pasture, pastoral communities are now struggling to survive amid the accelerating impacts of climate change.

Moroto District alone hosts an estimated 300,000 cattle, each requiring at least 15 litres of water per day, alongside more than 400,000 goats and sheep. At Kobebe grazing ground in Moroto District, over 50,000 cattle are now concentrated around a single shrinking dam, which has become the primary water source for pastoralists from across the region.

The Kobebe dam, once a critical lifeline, is rapidly drying up due to heavy siltation and the collapse of cattle watering traps. Pastoralists from Kenya’s Turkana region, Jie herders from Kotido District, and others from Napak District have all converged on the area, placing immense pressure on the limited water supply. As a result, livestock are forced to trek long distances in search of water and pasture, weakening animals and increasing losses.

Climate change has also introduced unfamiliar livestock diseases that pastoralists say are killing animals at alarming rates. Michael Achia, a herdsman from Kautakou Village in Napak District, says water scarcity, pasture shortages, and tick-borne diseases have become their biggest challenges. He explains that pastoralists are now competing with local communities for borehole water, which is designed for domestic use and is insufficient for livestock.

Achia says herders sometimes prioritise watering cows with calves to sustain milk production, leaving other animals without water. Over the past three months, he has lost five cows to suspected tick-borne diseases after the animals lost weight, began urinating blood, and later died. He has appealed to veterinary authorities to urgently investigate the outbreak and provide treatment.

Another pastoralist, Emmanuel Areman, says the situation worsens during dry seasons when most dams dry up quickly because they are shallow. He explains that pastoralists are forced to share water sources with communities, creating health risks for both people and animals. According to Areman, some herders with large cattle herds now walk more than 100 kilometres in search of water.

He adds that pasture scarcity has driven pastoralists to burn bushes in an effort to stimulate fresh grass growth and eliminate ticks hiding in dry vegetation, a practice that further degrades the environment.

Daniel Awas, a cattle keeper from Loputuk Sub-county, says climate change has devastated pastoral livelihoods, pushing many families into poverty and food insecurity. He explains that unpredictable weather patterns have made it impossible to plan for crop farming or livestock watering.

Awas notes that traditional water catchments, which once lasted up to five months, now dry up much faster due to intense heat. He adds that many pastoralists are migrating to regions such as Teso in search of water, increasing the risk of conflict over shared resources. Awas has called on the government to construct large, long-lasting dams to help communities cope with worsening climate conditions.

Women and children are also bearing the burden of water scarcity. Dorothy Namoe, a resident of Lotome Village in Napak District, says sharing boreholes with livestock has led to frequent breakdowns of water infrastructure meant for communities. She explains that some parishes have no boreholes at all, forcing women to walk more than 25 kilometres to fetch water from neighbouring areas.

Namoe fears the situation will deteriorate further as pressure on water sources increases. She adds that all water points in Lotome Sub-county have dried up, forcing men and boys to migrate long distances with livestock, leaving families behind and raising serious safety concerns.

Community leaders say adapting to unpredictable weather patterns has become increasingly difficult. Angella, an elder in Moroto District, says migration remains the only viable survival strategy for many pastoralists, but movement restrictions imposed by authorities have complicated access to pasture and water. He has urged leaders to engage neighbouring regions such as Teso, Lango, Acholi, and Sebei to allow resource sharing during extreme droughts.

Moroto District Veterinary Officer Dr. Moses Okino confirms that climate change has had a severe impact on livestock production due to shrinking pasture and water sources. He explains that droughts, which previously occurred every five years, are now more frequent, leading to poor pasture quality and increased water evaporation.

Dr. Okino says changing migration patterns have introduced new tick-borne diseases, first detected in Kenyan cattle and later spreading into Karamoja. He also warns of newly identified poisonous plant species in Rupa Sub-county, linked to climate change, which pose additional risks to livestock.

According to Dr. Okino, poor pasture nutrition has weakened animals’ immune systems, reducing productivity and forcing pastoralists to sell livestock at low prices to avoid total losses. He adds that some herders now water cattle only once every two days due to shrinking water sources.

Environmental advocates say climate stress is accelerating competition over natural resources. Frank Lopeyok, Executive Director of Karamoja Youth Effort to Save the Environment (KAYESE), says prolonged drought has worsened pasture scarcity while gazetted land under the Uganda Wildlife Authority has reduced available grazing areas.

Lopeyok notes that long treks in search of water have increased conflicts between pastoralists, conservation authorities, and neighbouring communities. He has called for the construction and rehabilitation of dams, as well as intensified community sensitisation on climate change. He adds that many residents still attribute climate change to spiritual causes. To help mitigate environmental degradation, KAYESE has launched a one-million-tree-planting campaign across Karamoja.

Moroto District Environment Officer Zackary Angella Lochoro says Karamoja once enjoyed reliable rainfall that supported both farming and pastoralism. He explains that early warning signs of climate change emerged between 2000 and 2010, marked by declining rainfall and worsening environmental degradation.

Lochoro warns that climate stress has pushed communities into charcoal burning as a survival strategy, further accelerating environmental destruction. He has called for stronger climate change awareness campaigns to help communities adapt and protect remaining natural resources.

The Sunrise Editor

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published.