Culture

Here are 10 “Dangerous” Tribes That Defy and Define History

From the depths of the Amazon to the plains of North America and the remote islands of the Indian Ocean, humanity’s history is interwoven with tales of indigenous peoples who have been labelled “dangerous.” This often-misunderstood designation, however, frequently reflects not inherent aggression, but rather a fierce determination to protect their lands, cultures, and very survival against external encroachment, disease, and exploitation.

Far from being mere relics of the past, these groups, some still uncontacted, others adapting to a rapidly changing world, offer vital insights into human resilience, diverse social structures, and the profound impact of colonialism and globalisation. This feature explores ten such tribes, delving beyond sensational headlines to understand the true nature of their “danger” and the enduring legacy of their struggles.

Here is the list

The Sentinelese and Jarawa

In the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, two tribes stand as powerful symbols of self-determination through isolation. The Sentinelese, inhabiting North Sentinel Island, are arguably the most isolated people on Earth.

Their millennia-long separation is evident in their distinct language and their unwavering, often lethal, rejection of outsiders. The 2018 death of American missionary John Allen Chau underscored their fierce resolve to remain undisturbed, a defence mechanism crucial for protecting them from diseases to which they have no immunity.

International indigenous rights organisations like Survival International advocate tirelessly for their uncontacted status, recognising that any forced interaction could be catastrophic.

Similarly, the Jarawa of Great Nicobar Island, renowned for their ancient hunter-gatherer traditions, historically defended their forest homelands with violent resistance against incursions like the Andaman Trunk Road. Their “danger” was a manifestation of their sovereignty.

While some Jarawa have recently initiated contact, this engagement raises concerns about cultural erosion and increased health vulnerabilities, highlighting the delicate balance between external pressures and their traditional way of life.

From Amazonian Warriors to Plains Lords: Yanomami, Comanche, and Apache

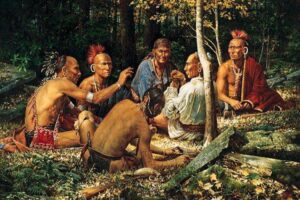

Across continents, other indigenous groups earned their “dangerous” reputations through powerful military prowess and unyielding resistance. The Yanomami of the Amazon, while celebrated by anthropologists, faced immense suffering from external contact.

YANOMAMI POUND LEAVES FOR TIMBî, DEMINI, BRAZIL

Their historical practice of “aggressive exo-cannibalism” can be seen as an extreme form of territorial defence, a practice that proved tragically insufficient against the diseases and violence brought by illegal gold miners in the 1980s, leading to devastating population loss.

Their ongoing struggle for land rights against continued illegal mining underscores the persistent threats they face.

In North America, the Comanche, known as the “Lords of the Plains,” transformed into a formidable warrior culture with the introduction of the horse. Their mastery of equestrian warfare allowed them to dominate vast territories for centuries, engaging in protracted wars against Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. forces.

Their “danger” was synonymous with their military might and adaptability, a force so fearsome that even the Apache, renowned warriors themselves, “were afraid of the Comanches.”

The Apache, expert guerrilla fighters of the American Southwest, leveraged their intimate knowledge of the rugged terrain to effectively counter superior forces. Chiefs like Geronimo became enduring symbols of indigenous resistance, employing “stealth and surprise to outwit powerful enemies.

” Their danger” was rooted in their tactical brilliance and their ability to inflict “terror and constant fear in the settlers,” a testament to their effectiveness in defending their lands and way of life.

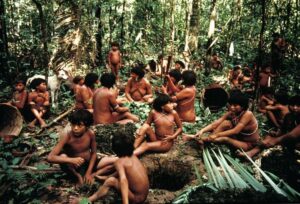

Strategic Alliances and Military Might: The Iroquois, Sioux, and Zulu

The Iroquois Confederacy, or Haudenosaunee, in North America, stands out for its sophisticated democratic governance and formidable political and military power. Described as “masters of stealth and unity,” they skillfully played French and English colonial powers against each other, maintaining strategic neutrality that preserved their influence for centuries. Their “danger” stemmed not just from martial prowess but from their highly organised political structure and diplomatic savvy, allowing them to expand their territory and exert considerable influence.

On the Great Plains, the Sioux are globally recognised through figures like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, whose decisive victory against General Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn cemented their fame. Their “danger” was inextricably linked to their fierce defence of sacred lands and traditional ways of life against relentless U.S. expansion, ignited by the discovery of gold in the Black Hills. Their resistance, though ultimately unsustainable against overwhelming force, became a powerful symbol of indigenous sovereignty.

In Southern Africa, the Zulu Kingdom under Shaka Zulu revolutionised warfare with a highly effective military organisation and innovative tactics. Their decisive victory against the British at the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879 marked one of the worst defeats a colonial power suffered at the hands of an African force. The Zulus’ “danger” was a direct product of Shaka’s military reforms and centralised political structure, enabling rapid expansion and posing a formidable challenge to colonial powers.

Cultural Resilience and Internal Dynamics: The Maasai and Huli Wigmen

While some tribes were defined by their resistance to external forces, others exhibit a “danger” more culturally embedded or focused on internal dynamics.The Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania are globally renowned for their distinctive cultural practices, particularly their “fierce warrior” ethos.

Maasai men are “born and raised to be Morans (warriors),” primarily responsible for protecting their cattle herds and community. Their “danger” is culturally embedded, focused on internal community protection and a strong warrior ethos, rather than external conquest. Their “fame” is primarily cultural, making them an enduring symbol of African heritage and resilience.

Finally, the Huli Wigmen of Papua New Guinea, famous for their elaborate ceremonial Wigs, demonstrate a distinct model of “danger” rooted in endemic internal warfare. Their society is explicitly described as a “war zone” where “revenge is more important than any peaceful settlement,” and leaders rise to power through “skill at war.” This highlights how conflict dynamics within indigenous societies can be complex and deeply integrated into social structure, distinct from the narratives of resistance against external encroachment.

These ten tribes, each in their own way, illustrate the diverse meanings of “danger” when applied to indigenous peoples. Their stories are not just historical footnotes, but living testaments to the enduring strength of cultural identity, the devastating consequences of forced contact, and the unwavering human desire for self-determination.

Comments