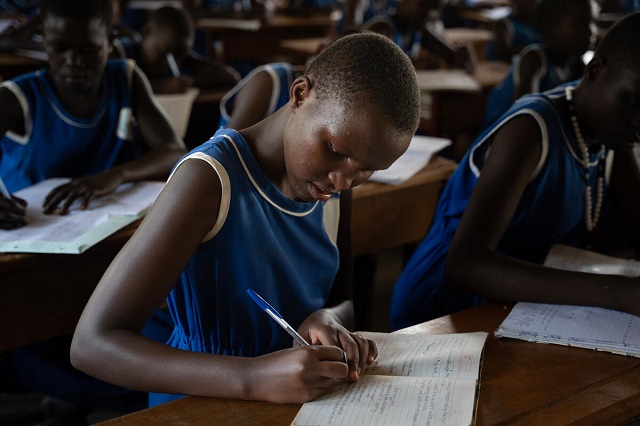

Education

Parental Negligence and Cultural Barriers Driving Karamoja’s Education Crisis

The persistent wave of school dropouts in the Karamoja sub-region is once again in the spotlight, with education authorities pointing a firm finger at parental negligence. While government interventions such as Universal Primary Education (UPE) and Universal Secondary Education (USE) have been in place for over two decades, the region’s dropout rates remain alarmingly high — in some districts, more than 40 per cent of pupils fail to complete the primary cycle.

At the heart of the crisis lies a clash between government-driven education initiatives and entrenched socio-cultural norms. In a region where cattle herding, mining, and subsistence farming dominate daily life, many parents see formal schooling as secondary — or even irrelevant — to their children’s future. Moroto District Education Officer, Italina Logwe, captures the problem bluntly: “We have cases where parents prioritise herding cattle or sending their children to the mines rather than school.”

The problem is particularly severe for girls. Early marriages, sanctioned by both cultural norms and economic desperation, rob many of the chance to complete even basic education. Kaabong DEO Santina Sandar notes that a lack of enforcement of child protection laws has allowed this practice to persist largely unchecked.

Even where schools are well-funded and adequately equipped, parental disengagement can still undermine progress. Lydia Wasula of the Ministry of Gender recounts that a school in Nakapiripirit, despite having resources, could only attract 40 per cent of its intended enrolment. This points to a deeper issue: education cannot succeed in isolation from community buy-in.

Cultural resistance plays a potent role. As Moroto’s Community Development Officer, Margie Lolem, explains, in some remote areas, education is still perceived as a “foreign concept” that erodes traditional values. For boys, cattle herding is seen as a rite of passage; for girls, domestic duties are prioritised over schooling.

While poverty is undeniably a contributing factor, it is not the only one. Amudat’s Commercial Officer Glaudy Auma points out that even in areas where school meals and materials are provided, many parents remain disengaged, believing education to be solely the government’s responsibility.

The result is a cycle that perpetuates low literacy, limits economic opportunities, and entrenches poverty. Without basic education, young people in Karamoja are left with few paths to sustainable livelihoods beyond the same subsistence activities that have defined the region for generations.

Breaking this cycle will require more than government policy and infrastructure. Authorities are calling for a multi-sectoral approach involving schools, parents, cultural leaders, and civil society organisations. Sensitisation campaigns that engage communities — particularly elders and clan heads — will be crucial in reframing education as compatible with cultural identity rather than a threat to it.

The challenge is as much about changing mindsets as it is about improving facilities. Until parents see the value of education in transforming not just individual lives but the entire community’s future, dropout rates in Karamoja are likely to remain stubbornly high.

Comments