Business

Silent inflation in Uganda

Companies have devised strategies of giving customers less quantities for the same or even more money!

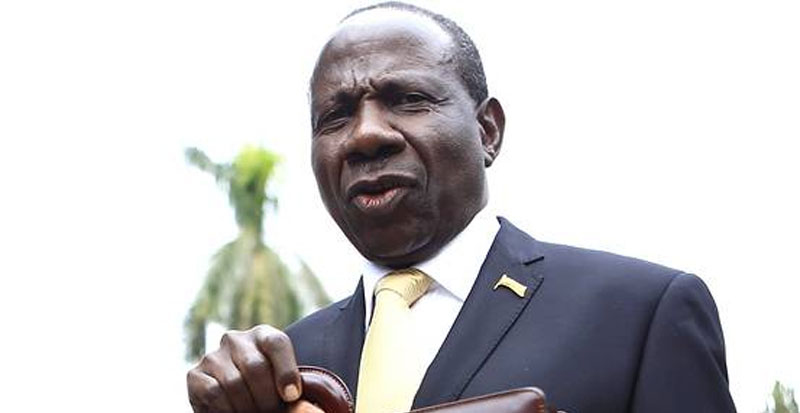

Minister of Finance Matiya Kasaija

This week, the MUBS Economic Forum – a think-tank I head at Makerere University Business School (MUBS) – hosted the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as they presented the Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa for 2019.

My good friend Clara Mira, the IMF Resident Representative in Uganda, presented a mixed bag for Africa. The global, regional and Uganda’s economies are on a recovery trajectory amidst rising risks. The average growth rate for the global economy in 2019 is projected to remain at 3.7% (the rate registered in 2017 and 2018), while Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is expected to grow at an average of 3.8% compared to 2.7% two years ago.

Uganda’s story is even more impressive. The economy is projected to grow at an average rate of 6% in 2019, mainly driven by services, manufacturing and construction. Some of the things that caught the audience’s eyes were the rising public debt almost everywhere, tightening financial conditions for countries, and as far as Uganda is concerned, the reported “contained inflation”.

One lady participant wondered why authorities in Uganda are more obsessed with containing inflation within target yet the cost of living has skyrocketed in recent years. Although Clara explained how inflation targeting has ensured that inflation is no longer a problem in Uganda, many in the audience, I inclusive were not fully convinced.

Giving customers less

Here is the puzzle. We have been led to believe (by the IMF, Bank of Uganda, UBOS and Ministry of Finance) that inflation in Uganda has been contained below the national target of 5%. The average headline inflation (the type that measures changes in prices of all items) for 2018 has been about 2.2%. Considering where the country was in 1980s and early 1990s when official inflation was in triple digits, and recently between 2008 and 2012, that seems impressive.

However, translating these annual inflation targets to longer-term inflation changes the whole picture and forces one to pull off their dancing shoes. The reality is that we (and I guess even ‘experts’ at IMF, BOU, UBOS and MoFPED) are being “silently” fooled into thinking we’re stable inflation means Ugandans are getting value for their money.

We need to start looking at inflation this way: inflation of 2.2% per year implies 22% inflation over a decade, or 81% inflation over 30 years. Yet average annual inflation in Uganda has actually been much higher than that.

Since 2008, annual inflation has averaged 9.6% which translates into 96% increase in prices of goods and services over the past decade. This is one of the reasons Ugandans feel their cost of living has significantly increased, contrary to the reported “stable” or “contained” inflation.

A 350mls coke is now at 1,200

Another reason is even more interesting. Rather than raising prices to match the long-term increase in inflation, companies have devised strategies of giving customers less quantities for the same or even more money. A perfect example is soda whose quantity has been reduced from 500ml to 350ml bottles (in some countries they sell even much smaller bottles – 150ml), to play around with consumers’ psychology.

The 500ml bottle now costs Shs. 1500

What is silent inflation?

The logic is to dupe the customer that the price of soda has not changed much. For example, the money that purchases a 350ml bottle of coke (mini) today could buy us half a litre (500ml) bottle ten years ago. Actually a half litre bottle of coke cost Shs. 900 in 2008 yet coke-mini (350ml) costs Shs.1200 today. The 500ml bottle now costs Shs. 1500.

When you factor in these cost cutting measures, you realised that the rate of inflation is actually much higher than what UBOS reports. This is what economists call “silent inflation”. It causes a sort of magnification of the present in the minds of most people and they forget about the long term impact. With silent inflation, it can be easy to forget that the truth is much less dramatic.

What is more intriguing is that silent inflation is not only prevalent in poor, inflation-prone countries such as Uganda. Robert Shiller, a Professor of Behavioural Economics at Yale University in the US and a 2013 Nobel laureate in economics, recently penned a revealing article about silent inflation in rich countries.

Before his eye-opening article, many used to think inflation in countries such as the US, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, and the United Kingdom was an irrelevant macroeconomic variable. In these countries, and many other developed nations, annual inflation is targeted at below 2%.

BOU introduced inflation targeting in Uganda in July 2011. I have for years been writing, in these very pages, about the need to rethink, not only this monetary policy framework but also the overall mandate of the BOU.

BOU Mandate

Under Mutebile’s reign, BOU has been an inflation ‘targeter’. He trained his officials to argue that achieving price stability on the order of low inflation, results in achieving other goals of the economy. But this hypothesis is conflicting with empirical evidence and on-the-ground realities in Uganda.

A day after IMF’s presentation, I attended the NTV organised Economic Summit under the theme: “Key policy triggers for economic growth with jobs.” I am quite a vocal economist, but this time I chose not to speak but listen to what other participants (mainly non-economist CEOs) had to say about this important topic.

Most of the views were advocating for actions to bring growth back. Those bored me because although growth is conventionally known to create jobs and reduce unemployment, the experience in Uganda has been different.

Empirical and diagnostic studies show that Uganda’s growth profile has in the past remained jobless. Bering one of those who have analysed and interrogated this paradox, at the beginning I was bored when I heard participants, one after another advising Ministry of Finance to do the same things they’ve been doing in the past leading to jobless growth.

The day was saved towards the end of the conversation when Patrick Ayota, Deputy Managing Director of National Social Security Fund (NSSF), asked government to do what we have been singing for years – change the mandate of BOU.

Uganda’s main growth drivers and spoilers

Evidence shows that in many countries that created “growth with jobs” — including Japan, South Korea, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, the U.S., and West Germany — their central banks directed credit to develop industries and small businesses during their rapid industrialisation phase.

Like I have severally written before, BoU needs to actively direct/influence credit to flow to our fledgling manufacturing industries as well as towards raising agricultural productivity through financing of adoption of new technologies, post-harvest management and value addition, beyond their derisory agriculture credit facility (ACF) which obviously will never work.

Elly Karuhanga and Prof. Samuel Sejjaka also saved the day when they respectively called upon Finance to invest in people (education and skills), fine-tune industrial policy, regulate the economy, and deal with fiscal indiscipline.

Had I chosen to speak, I wanted to ask the following questions: what are Uganda’s main growth drivers and spoilers? How tradable/exportable are they? Are they the sectors that the current economic policy is pursuing? Was their selection informed by empirical research, politics or emotions? Which sectors or industries should Uganda invest in to achieve both growth and jobs?

I know lists of sectors and enterprises have been selected by various MDAs – ranging from agricultural value addition to tourism and textile and leather industries. What informed their selection? Was the selection criteria empirically informed? If so, how can these sectors/enterprises be unlocked and developed to maximise both output and job creation? Who should do what in government, private sector, civil society and development partners?

These are questions which conversations such as NTV Economic Summit should be discussing. Obviously to have a constructive conversation, there is need to first put together an empirical analysis that investigates those questions. Thankfully, I am part of a team that is currently trying to put together such as analysis. We hope its findings will help to add value to this conversation.

Comments