Politics

Betting on Biometric Voting: Lessons from Africa

As Uganda prepares for the 2026 General Elections, a quiet revolution is taking shape, one driven not by new faces or campaign promises, but by technology and the law.

In what could become the most consequential legal amendment ahead of the polls, the Government is seeking to make Biometric voter verification compulsory. The shift will change the way Ugandans vote.

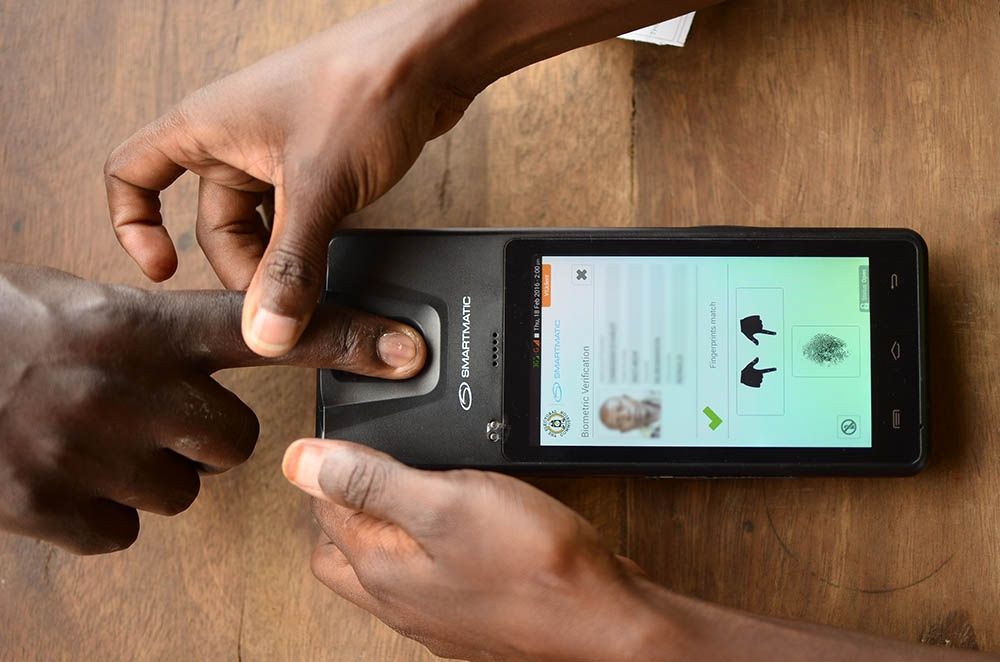

Already partially in use, the Biometric voter system allows for fingerprint-based verification at polling stations. However, under current laws, this verification remains optional, allowing for a fallback to manual registers. Critics say this fuels electoral fraud, multiple voting and ghost voters.

The Justice and Constitutional Affairs Minister, Mr. Norbert Mao, while addressing journalists during the ground-breaking of the new Electoral Commission (EC) headquarters last week, said that the Government is determined to shut that door.

“We’re not introducing something new. What we’re doing is removing the option of by-passing the system. Once this becomes law, no Ugandan will vote without Biometric identification,” Mao said during a press briefing. He added that the proposed amendment also creates criminal liability for electoral officials overseeing discrepancies between machine records and physical ballots.

Justice and Constitutional Affairs Minister, Mr. Norbert Mao

The amendment is currently under review by a Cabinet subcommittee led by Information, communication and Technology (ICT) Minister, Mr. Chris Baryomunsi. Once approved, it will be tabled in Parliament for debate and passage.

Among the most notable elements of the proposed law is a five-year prison sentence for presiding officers, or returning officers, found culpable in ballot-machine mis-matches, especially in cases where the number of ballots in the box exceed those registered on the Biometric machine. “This is designed to stamp out ballot stuffing and restore confidence in the vote,” Mao emphasized.

Electoral Commission in Preparation

The Chairperson of the Electoral Commission (EC), Justice Simon Byabakama, also confirmed that the EC is already moving ahead with procurement based on the assumption that the law will pass.

“We are not waiting for the law to catch up. We are preparing for a full biometric process. We cannot afford to be unprepared,” he said, adding that, “The Constitution, under Article 61, doesn’t give us an option to delay elections.”

Byabakama disclosed that at least two Biometric kits will be deployed per polling station in line with international best practices, notably Ghana, to ensure continuity in case one machine malfunctions.

With over 36,000 polling stations projected, the logistics will be massive. Already, the EC has budgeted close to UGX. 70 billion for Biometric kits alone, with additional costs for training, support infrastructure and back-up systems.

Chairperson of the Electoral Commission , Justice Simon Byabakama

Uganda to Prepare to Deliver

Election experts say the Government’s plan is ambitious but necessary. “You cannot run credible elections on a system that allows manual by-passes,” says one of the experts. “Biometric verification, if implemented fully and transparently, can limit fraud. But it’s only as strong as the systems and people operating it.”

They warn however, that Uganda must prepare for rural deployment challenges, including a lack of power, internet connectivity and skilled personnel. Regional experiences indicate that across Africa, Biometric voting systems have been adopted with varying degrees of success. Uganda has the opportunity to learn from its neighbours.

Kenya: Double-Edged Sword

Kenya was among the first in the region to adopt the Biometric technology in 2013 through the use of Electronic Voter Identification Devices (EVIDs). While the move was hailed as a game-changer, implementation has been marred by technical breakdowns, resulting in widespread fallback to manual voting.

In 2017, Kenya rolled out the Kenya Integrated Election Management System (KIEMS). Though more reliable, the Supreme Court still annulled the presidential results due to irregularities in transmission. Reports indicate that in Kenya’s case, the technology was good, but the execution and communication were poor. There was a big gap in technical know-how.

Tanzania: System Stuck in Limbo

Tanzania introduced the Biometric voter registration in 2015, but the system’s impact has been muted. While voters are registered biometrically, manual registers are still commonly used on Election Day.

In 2020, critics accused the National Electoral Commission (NEC), of limiting transparency and relying too heavily on manual systems, undermining the trust that Biometric registration was meant to inspire.

Nigeria: BVAS Battle for Credibility

Nigeria’s Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS), is perhaps the most aggressive Biometric deployment in Africa. Introduced in 2021, BVAS uses both fingerprint and facial recognition to accredit voters and transmit results electronically.

The 2023 elections saw extensive deployment of BVAS, but not without issues. There were glitches in result transmission and accusations of system manipulation. “BVAS drastically reduced multiple voting, but system crashes and lack of transparency in transmission hurt its impact,” noted Nigeria’s Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD).

Despite the criticism, Nigeria’s Biometric approach is seen as a bold template for emerging democracies, showing both the promise and the limits of technology in elections.

Ghana: Gold Standard for Backup

In 2020, Ghana deployed two Biometric kits per polling station to prevent delays and ensure seamless verification. The elections proceeded smoothly, with minimal disruptions—setting a regional benchmark for Uganda to consider.

What do Ugandans Know?

On the streets of Kampala, the proposal has received mixed reactions. While some citizens applaud the move as necessary for clean elections, others are sceptical about its execution. “It’s good if it works. But in my village, we don’t even have stable electricity,” says Ms. Joyce Akiteng, a farmer from Amuria. “What happens if the machines break down? If, even when a transformer replacement takes months to be repaired.”

Others like Mr. Brian Okello, a first-time voter in Nansana, believe the changes could restore faith in the system: “This is going to be my first time, but I’m yet to know about this system. If everyone is verified and no ghost voters sneak in, then my vote counts. That’s what I want to see in 2026.”

Mr. Henry Kamanzi, a politician, argued whether the EC has fully trained the polling agents who are going to use them. “You remember what happened to the Uganda Bureau of Standards (UBOS)? Some enumerators did not even know how to operate these machines, and others were faulty. So, let me hope this time it’s going to be a different story.”

However, to settle Kamanzi’s fears, Byabakama assured Ugandans that the equipment to be used in the coming General Elections is new. The EC is pressing ahead and the Government ministers insist the legislation will be tabled before the end of the year to give time for adjustments.

If all goes to plan, Uganda would join the ranks of African nations taking bold steps towards transparent, technology-driven elections. But whether the gamble pays off depends, not just on machines and laws, but also on political will, community buy-in and competent implementation.

However, it must be noted that Biometrics are not magic bullets. They must be part of a broader strategy of civic trust and institutional accountability. With time ticking and costs rising, Uganda now stands at a crossroads between electoral reform and logistical risk. This is a test, not just of its technology, but of its commitment to democracy itself.

Comments